Wet Streets Cause Rain

Book Review: The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America - and How to Undo His Legacy

William Zinsser once observed that good nonfiction is often dependent on the writer’s ability to supply the reader with surprising or interesting facts. The biggest strength of The Man Who Broke Capitalism is that its author, New York Times journalist David Gelles, has a knack for pulling out anecdotes and data points that make you question everything you think you know. For example, at one point, the book states:

Had the federal minimum wage simply kept up with inflation since 1968, it would be more than $24 an hour.

I don’t know about you, but when I read that sentence, I stopped in my tracks. I thought to myself: “wow, that’s unbelievable”!

Then I thought to myself: “Wow, that’s really unbelievable”. So I plugged it into Google and I got this:

$12 an hour. A much more believable figure, and mathematically, only half of $24. I’d love to say that this slip-up was a one-off, but sadly, most of the interesting “facts” in the book didn’t survive a quick check on Google. Writing good nonfiction: harder than it looks!

I’ve run an occasional series here reviewing books about the demise of GE. At its peak in the early 2000s, GE was the most valuable and most respected company in America, but it imploded over the following decade and has since been broken up. It’s the kind of extreme outcome that exposes important lessons about investing and management, and the books reviewed here were all well researched and insightful.

I first read The Man Who Broke Capitalism when it was released three years ago. I must confess that I was initially unimpressed: I dismissed it as standard issue airport slop, appealing to midwits that read the New York Times, but of no real interest to the refined intellects that read this blog. (I’m kidding, of course: I totally discovered the book when it was excerpted in the New York Times, which is a publication that I, a certified midwit, read on a daily basis.) Also, writing a book is hard (I imagine), and it seemed ungenerous to write a review of a book with the sole intent of tearing it to shreds.

Still, I had the nagging feeling that something was missing from the other books I reviewed about GE. Finally, I had an epiphany. I’ve been reviewing smart books about an all-time act of stupidity. As good as those books are, one would have to agree that there is some dimension of stupidity that a smart book simply cannot access. So here I present my review of The Man Who Broke Capitalism.

The thesis of The Man Who Broke Capitalism is bluntly stated in the subtitle: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America — and How to Undo His Legacy. The deindustrialization of the Upper Midwest, widening income inequality, growing corporate malfeasance: every modern economic ailment can be traced back to 1981, when Jack Welch was appointed as CEO of General Electric.

The theory here is that the period from 1945-1980 was a golden era for the American worker simply because American corporate culture was better back then. Executives paid their employees generously, eschewed layoffs, and cared deeply about their duty to their communities and their country — even if it came at the expense of corporate profits and CEO paychecks. Then Jack Welch came along and destroyed all of that. He shut down factories and shipped jobs overseas and used the profits to buy back stock. Other greedy CEOs followed his example, spreading “Welchism” throughout the American economy. In Gelles’s opinion, to save the economy, we must RETVRN to the culture of the 1950s: if CEOs would just stop laying off workers and cease buying back stock, the factories would reopen, income inequality would abate, and we would enter a new economic golden age.

Gelles actually does identify some (real) evidence that seems to support his theory. He observes that total US manufacturing employment peaked at around the time that Welch took power at GE, and has been declining ever since, particularly in the Upper Midwest, where GE had a large presence. Stock buybacks were almost nonexistent before the early 1980s, but are ubiquitous today. Executive compensation is much higher today than it was in the early postwar era. Is it possible that Gelles has picked up on something that legions of experts have missed over the decades?

The answer: of course not. Upon closer inspection, the evidence he cites is badly misinterpreted, and his analysis is hopelessly confused and naive.

Let’s start with the claim that manufacturing employment peaked around the time Welch became CEO of GE. This is technically true: in absolute terms, the BLS says that manufacturing employment in the US peaked in June 1979, shortly before Welch took the top job at GE in 1981.

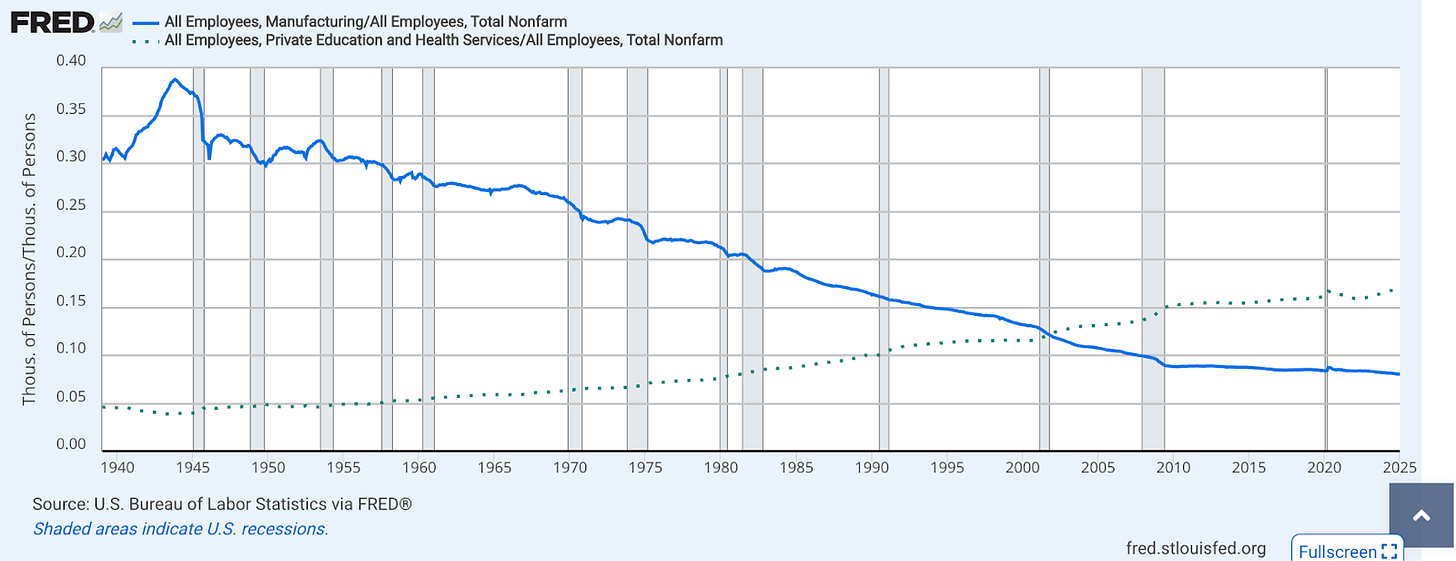

The problem with this measure is that manufacturing employment had been steadily shrinking as a share of total employment since 1950. If we want to understand how the economy is evolving, we want to look at the share of workers in each sector, not the absolute number, which is also influenced by demographic fluctuations that grow or shrink the overall workforce.

Even though manufacturing employment had been holding steady from 1950-1979, this happened against the backdrop of a rapidly growing total employment, as baby boomers flooded into the workforce and women began working in much greater numbers. Here is a chart showing the share of American employees working in manufacturing1 since 1939: there was not much of an inflection point after 1981 (beyond the recession), just a steady decline since the 1950s.

Unlike the “golden era” thesis, this actually matches contemporaneous accounts. In 1986, David Halberstam published The Reckoning, a detailed account of how the Japanese auto industry caught up to Detroit, culminating in the 1979 energy crisis and subsequent mass layoffs at the major American automakers, who were caught without any competitive fuel efficient cars to sell.

Incidentally, the 1979 energy crisis was the real shock to Midwestern manufacturing, and it pre-dated Jack Welch. According to Cleveland Fed economist Mark Schweitzer, the industrial heartland lost 1.2 million manufacturing jobs between 1979 and 1983, over 20% of the previous manufacturing workforce. He finds that manufacturing employment in that region actually held flat between 1983 and 2000 (the Welch era), before declining again after 2000.

Halberstam interviewed Detroit residents in the grim winter of 1982, when local unemployment reached 16% and droves of laid-off autoworkers were fleeing to take part in the energy boom in Texas. There he discovered a general awareness that manufacturing had been losing ground to services in America for decades. Halberstam found it symbolic that the local Detroit sports teams had all once been owned by manufacturing tycoons, but lately the Tigers (baseball) and the Red Wings (hockey) had been sold to two local pizza entrepreneurs, Tom Monaghan (Domino’s) and Mike Ilitch (Little Caesars). From the vantage point of people living in the early 1980s, American manufacturing peaked before 1950, and had been steadily shrinking in importance ever since.

The Reckoning does not position the 1950s as a golden era; on the contrary, the 1950s are framed as the source of original sin, when Detroit sowed the seeds of greed and complacency that it would reap three decades later. (You might have guessed that much from the title.) At that time, the Big Three automakers functioned as a cozy oligopoly, with too much scale to ever be threatened, churning out giant gas-guzzlers that were forced on captive consumers at inflated prices.

True, the unions ensured that the workers were paid well, but this came at the expense of other American workers who were forced to pay more for their cars. Schoolteachers and clerks were gouged and the unions divided the spoils with wealthy shareholders and private-jet flying executives. At one point, Halberstam describes a scene in 1946 in which Walter Reuther, the principled head of the UAW, demands a wage increase, but with an additional condition: the auto companies would eat the cost of the pay hike via reduced profits, instead of passing it along to consumers. The auto executives respond that they are willing to grant the wage increase but they will not be told how to pay for it, and after some consideration, Reuther reluctantly accepts. It is suggested that from that point forward, the union becomes complicit in the whole doomed arrangement.

None of this is to say that Halberstam’s narrative is entirely correct, and he himself acknowledges that there were other forces at work that caused the decline of the American auto industry. But it is notable that people in the 1980s seemed to have a much clearer view of the timing and causes of deindustrialization, while modern commentators who venerate the immediate postwar era often get the facts and timelines hopelessly garbled.

The theory that the 1950s were a golden era of corporate investment, one that came to an end with the advent of stock buybacks in the 1980s, is similarly without merit. We have talked about stock buybacks at length before: they are nothing more than a substitute for dividends, a more flexible way to return cash to shareholders that doesn’t entail the same implied commitment that a regular dividend does. In substance, the shift from dividends to stock buybacks is simply a case of moving from six of one to half a dozen of another.

Dividends and buybacks are substantially economically equivalent: an investor who uses the dividends that she receives to buy more stock (as we all do in our 401ks, by default) ends up in almost the exact same place if a company chooses to withhold all dividends and uses the cash to buy back stock (on behalf of her and her co-investors).2 In both cases, excess cash ends up in the hands of investors who want out, and the remaining shareholders own a larger stake in future cash distributions.

We previously found that companies had always retained whatever cash they felt they could invest productively, which for mature companies was generally 20%-40% of earnings. The remaining 60%-80% was returned to shareholders in the form of dividends, to reinvest in other productive projects (or to consume). GE followed this pattern closely: the above graph from GE’s 1960 annual report shows that GE had paid out 67% of earnings as dividends throughout its history to that point, dating all the way back to 1899.

In the 1980s and 1990s, companies started cutting dividends and redirecting the extra cash toward stock buybacks, and today, companies pay out about 30% of earnings in dividends and about 40% in buybacks. Here, GE simply followed the broader corporate trend of the time. GE’s 2000 annual report, the last of Welch’s reign, shows that over the previous three years, 44% of earnings went toward dividends, while 28% of earnings went toward net buybacks, for a total payout ratio of 72%, about the same as it had been for the previous century.

The funny thing is, Jack Welch hated stock buybacks. As William Cohan wrote in Power Failure, Welch (wrongly) believed he could create more value by using spare cash for acquisitions. In the late 1980s, he caved to investor pressure and started buying back stock. Part of the idea behind dividends and buybacks is to restrain CEOs like Jack Welch; if Welch had been able to retain (and squander) earnings as he pleased, GE would have been an even bigger disaster.

The idea that the 1950s were a period of especially high corporate investment is also contradicted by the data; in fact, it is the opposite. In aggregate, business investment, defined as spending by private businesses and nonprofits on structures, equipment, and intellectual property, was only 10%-11% of GDP in the 1950s, a figure that has risen to 13%-14% of GDP today.

Again, the anecdotes match the data. Remember, people in the 1980s were bemoaning how the big automakers squandered their mid-century advantage by underinvesting in research and development, not managing to design a single competitive small car between them. At GE, journalist Thomas O’Boyle found that management shut down a lot of promising research projects in the 1950s, which caused many of their best scientists to flee to Motorola.

The corporate culture in modern big tech is almost the exact opposite, to the point where a hugely profitable company like Amazon won’t return a dime to shareholders year after year and is applauded by Wall Street, and the CEO of Microsoft will casually drop that he is “good for $80 billion” in AI investment this year.

As an aside, Gelles seems to be confused by the entire concept of profit and private investment, which in fairness is commonly misunderstood. He bemoans the fact that “[b]efore Welch, corporate profits were largely reinvested in the company or paid out to workers rather than sent back to stock owners…[after] Welch, a greater share of corporate profits was going to investors and management.”

First of all, corporate profits are what’s left over after paying management and workers, so neither statement makes any sense. Putting that aside, corporate profits reinvested in the company still very much belongs to stock owners. That’s what private investment is — you put in money today in the hopes that you can take out more money tomorrow. If Apple invests money today to develop a new iPhone, their stock owners will profit tomorrow when that iPhone is sold to consumers at a profit. If stock owners want to take cash out of the company in the form of buybacks and dividends, it is because they believe (rightly or wrongly) that they can invest it more effectively in outside projects than management can invest it in internal projects. It is not less greedy (or more greedy) to invest retained earnings internally.

Finally, the idea that the GE of the 1950s was a model of corporate citizenship is pretty laughable. In fact, GE in that era was so corrupt that they were caught leading one of the biggest price-fixing rings ever, a scandal that Fortune dubbed “The Incredible Electrical Conspiracy”. That case, in which the co-conspirators rigged the bidding process for electrical equipment, ultimately raising electrical bills for ordinary Americans, resulted in three GE executives being sent to prison and a round of highly publicized congressional hearings.

John Brooks wrote a hilarious article for the New Yorker reporting on those hearings, in which it became apparent that GE’s participation in the fraud was sanctioned by its senior-most executives. However, it also became clear that the top brass at GE had the foresight to create enough plausible deniability so that if the hammer fell, they could plead ignorance and make their underlings take the blame — which is exactly what they did.

This led to a farcical display in which a parade of GE divisional managers, all making over a million dollars a year (in 2025 terms), unanimously insisted to Congress that the criminal conspiracy for which they had recently been convicted of spearheading was actually just a huge misunderstanding, nothing more than a series of innocent miscommunications between a bunch of bumbling but well-intentioned middle managers. The Congressmen running the hearings understandably found this position implausible and insulting, which led to exchanges like this:

SENATOR KEFAUVER: Mr. Vinson, you wouldn’t be a vice-president at $200,000 a year [over $2 million in today’s money] if you were naive.

MR. VINSON: I think I could well get there by being naive in this area. It might help.

Gelles concludes by profiling two companies which he feels best exemplify the book’s thesis and a better path forward: Unilever and PayPal. He argues that the chief executives of these two companies rejected the pressure to lay off workers and limit wage growth and both companies thrived as a result.

This seemed to be true at the time of the book’s publication in early 2022, but since then, both companies have struggled mightily, and both have been forced to undergo GE-style layoffs and restructuring. Under pressure from activist investor Nelson Peltz (who a few years prior also targeted GE), Unilever has engaged in successive rounds of management layoffs to reduce bloat, most recently announcing plans to cut 6% of its workforce and spin-off its ice cream business. For its part, PayPal eliminated 7% of its workforce in 2023 and cut another 9% of its workforce in 2024.3

Why doesn’t Gelles’ thesis align with the evidence? Intuitively, his logic seems very compelling, and almost tautological. If manufacturing employment is falling, and corporate executives determine how many manufacturing workers to hire, then reversing the decline is a simple matter of jawboning:4 pressure CEOs to hire more workers, and domestic manufacturing will rise again. Judging by the popular response, readers seem to agree: the book was an NYT bestseller, and has thousands of glowing reviews on Amazon and Goodreads, describing the book as provocative, insightful, and even profound.

The fundamental problem with the theory is that it’s kind of — how do I put this politely? — completely ludicrous? The implicit model of the economy here is that CEOs decide how many people to hire and what they get paid and their actions determine economy-wide incomes and corporate profits. But that’s not at all the system we live in. In reality, we, as consumers, pay the wages of the workers that provide our goods and services. We choose what products we want to buy, and the businesses that make those products take the money we give them and use it to pay wages and suppliers, with a sliver left over for profit. (In manufacturing, profit margins average around 9%.) Companies pay their workers, but we are the ones who decide which companies get paid.

Corporate managers have some discretion, but they work within very tight constraints, largely determined by consumer tastes, technology and competition. Consider GE’s housewares division, which at the time of Welch’s appointment made small electrical appliances like toasters and curling irons, mostly right here in the USA. In 1982, Welch shut down an uncompetitive steam iron factory in Ontario, Calif. that prompted 60 Minutes to accuse him of putting profits before people, and in 1983, he sold the whole housewares division to Black and Decker.

Housewares aren’t often manufactured in the US anymore. Apparently, 99.5% of our toasters today are made in China, something J.D. Vance made a campaign issue.5 Is this Jack Welch’s fault? Probably not. Welch claims to have simply foreseen that housewares had no barriers to entry and would eventually be overrun by cheaper competition from Asia, and sold the business when Black and Decker showed an interest. Whether or not he saw the future as clearly as he claimed, Welch was correct that the long-term future of housewares would mostly be determined by external shifts in technology and trade that would permanently change intrinsic economics of the business, and not by anything corporate managers could do.

The location of physical manufacturing tends to be a function of the characteristics of the product itself — labor input, transportation costs, tolerance of long turnaround times, supplier networks, and so on. Executives have to make some predictions — will people pay a premium for a Made in the U.S.A. toaster? — but over a longer period of time, consumers vote with their wallets, and companies that make bad predictions will eventually be forced to exit their bad bets.

If all toasters today are made in China, after having previously mostly been made in America, that probably tells us more about the nature of toasters and the demands of American consumers than it does about Jack Welch, in the same way that domestic assembly of foreign cars tells us more about the nature of cars than it does about the pro-U.S. attitudes of foreign auto executives.

Gelles would have done well to review the extensive literature on deindustrialization.6 Economists that seriously study the issue generally find that falling manufacturing employment doesn’t have much to do with corporate management, and surprisingly, it doesn’t even have that much to do with trade (although a few dissent on this latter point). Instead, 80% - 90% of the decline can be traced to higher manufacturing productivity combined with stagnant demand, the same thing that reduced employment in agriculture in a previous generation.

This is why the decline in manufacturing employment dates all the way back to WWII: greater manufacturing efficiency generally translates to lower manufacturing employment, because there is some upper limit on the number of cars and light bulbs we want to consume. We take the dividends from more efficient manufacturing and redeploy it to deliver services, especially in education and health care:

Jack Welch may be guilty of many sins, but he is probably off the hook for destroying manufacturing employment in the Upper Midwest. The timing doesn’t line up, and the American shareholder capitalism thesis hardly explains why almost every major industrialized country has a rust belt. The Man Who Broke Capitalism pushes an appealing narrative, but falls apart under any kind of scrutiny.

The Man Who Broke Capitalism is a prime example of what the late Michael Crichton dubbed Gell-Mann Amnesia:

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray's case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward — reversing cause and effect. I call these the "wet streets cause rain" stories. Paper's full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

The Man Who Broke Capitalism is very much journalism of the “wet streets cause rain” variety, just expanded into a book. In this particular case, the causal relationship isn’t precisely reversed, but it is totally misidentified: Gelles has sectoral employment being dictated by executive fiat, rather than by consumer demand. (Although you could go one step further and hypothesize that the decline of American manufacturing led to executives like Jack Welch, rather than the other way around, in which case his theory actually would be exactly backwards.)

It seems unfair to single out one book or one journalist for bad economic reasoning, when similarly misguided articles and books come out with such regularity. Almost thirty years ago, Paul Krugman wrote an eviscerating review of a widely lauded pop-econ book written by a very serious journalist who committed the same logical error as Gelles did here — the fallacy of composition — a book which also apparently contained a number of incorrect “facts” as well as the mistaken conclusion that we would imminently stop creating new service jobs. (Nope, not yet, not by a long shot.) Thirty years from now, journalists will still be writing pop-econ bestsellers with the same elementary mistakes and those books will still be received with widespread praise.

In the last edition, we talked about the importance of paradigms in facilitating our understanding of the world. A paradigm, as defined by Thomas Kuhn, is a unified predictive framework that explains what we observe in a given field; for example, after Copernicus and Galileo, astronomers used a heliocentric model of the solar system to predict the positions of the planets. Kuhn explained that even smart people tend to get locked into obsolete paradigms (like geocentrism) — paradigms that are completely backwards, and contradicted by the facts — because these paradigms also dictate how we perceive and evaluate new evidence and thus prevent us from updating our beliefs.

If you look at a job posting for a journalist at a top newspaper, you see a lot of reference to ability to tell stories and cultivate sources, but almost never any requirement that the journalist have any education in, or real understanding of, the field that they will be covering. In theory, this gives reporters the advantage of impartiality — as an outsider to the field they are reporting on, they can approach it with a skeptical eye — but in practice, it is hard to accurately describe something you don’t really understand. And there is no reason to believe that a journalist will gain an understanding of a field simply by reporting on it over time. Remember, we tend to get locked into long-held paradigms without even being conscious of it.

This goes some way to explaining the phenomenon of Gell-Mann Amnesia: no matter how much time and effort a journalist puts into reporting a story, the story will end up being shaped by the paradigm in the journalist’s head. This is true even if the journalist consciously avoids analysis — every story has to package the facts one way or another. If the paradigm is backwards, the story will be backwards. Hence the proliferation of books and articles by experienced journalists that confidently assert that wet streets cause rain.

This brings us back to Gelles’ howler at the beginning, the claim that the federal minimum wage used to be $24 per hour, adjusted for inflation. The popular claim that journalists are lying liars who are out to scam the public is greatly mistaken. Journalists, like all of us, see what they expect to see. It is actually easy to trace the source of this particular error: a think tank pushed a widely-disseminated claim that the minimum wage would have been $24 per hour if it had “kept pace with productivity”, a calculation which was itself the product of a spreadsheet error and incorrectly mixing price indexes.

One can understand how a well-intentioned writer might come across a good factoid, misinterpret it, and publish the result because his mental model of the world told him it was almost certainly true — people tend to overestimate the living standards of the past. Once we think we have a good framework for understanding something, our brains are very good at hallucinating “facts” that fill in the gaps.

At this point you might be thinking, hang on, Not All Journalists. Which is true! A few reporters, like John Brooks, manage to get the key frameworks of the field they cover straight in their heads, even if they don’t know the details like an expert. But for every John Brooks there are a dozen other business journalists who regularly mix up basic concepts like revenue and profit. Again, journalists are hired for a different skill set.

It is hard to blame newspapers or journalists for this state of affairs. Exclusively hiring journalists with subject matter expertise would undoubtedly be much more expensive, and it is not clear that enough mainstream newspaper subscribers would pay a significant premium to read such a publication. Nor is it clear that it is even possible to hire very many people who have subject matter expertise and the ability to write clear, readable prose and the ability to source and report relevant stories, at any reasonable price.

Gelles starts to pull at an interesting thread at one point in the book: he observes that even though most of Welch’s proteges crashed and burned after leaving GE to take other CEO jobs, a few rejected the philosophy of their mentor and went on to great success in their new roles. One might ask: what would cause them to reject the teachings of the great Jack Welch?

We have talked before about Welch’s philosophy, which could be summed up as: “find a way to report quarterly earnings that move in a smooth upward trajectory, and success will follow”. One can understand the basic intuition: executives observe that companies like Coke and Microsoft report quarterly earnings that move in a smooth upward trajectory, and investors award them with a premium valuation. They also notice that when they report a bumpy quarter, investors get really mad. Therefore, the solution is to synthetically create earnings that move in a smooth upward trajectory (ideally while beating sandbagged earnings per share estimates by a penny every quarter), which will garner them a high stock valuation and perpetually happy investors.

This is very much a “wet streets cause rain” view of the world. In reality, building and operating a successful business is what leads to sustainably growing quarterly earnings, not the other way around. Look at the most successful businesses in modern Corporate America, companies like Apple, Google, and Berkshire – how much effort do any of them put into managing or smoothing their quarterly earnings?

Even if earnings smoothing were mostly benign, it is difficult to see how it could possibly be in the interest of long-term investors. Over longer holding periods, total investor returns are chiefly determined by the cash that a business generates for its shareholders and how that cash is invested, and have very little to do with the stock valuation in the meantime. In fact, a higher valuation actually works against the interest of long-term investors that plan to reinvest their cash distributions along the way, forcing them to buy stock at inflated prices. GE’s brief period trading at a 50x PE in 2000 did absolutely no good for any long-term shareholder that stuck with the company.

In practice, earnings smoothing is not benign at all, as Welch’s GE tenure demonstrated. Good accounting is part of the feedback loop that managers rely on to identify and solve important problems. To paraphrase Buffett, the problem with bad accounting is not just that management is lying to investors, it is that management is lying to themselves. Cohan’s Power Failure is replete with anecdotes where a narrow focus on hitting quarterly earnings targets resulted in real damage to the business, culminating with one memorable tale where GE sold a power plant on credit in Angola to book earnings for the quarter, with little hope of ever collecting any cash.

GE’s core industrial businesses were cyclical in nature, so to create smooth earnings, Welch bought into businesses that had a lot of short-term accounting discretion — mostly in finance and insurance.7 When the industrial businesses produced a shortfall in a quarter, Welch could book an offsetting gain by selling an appreciated real estate asset or reducing insurance reserves, and keep overall earnings on track.

However, finance and insurance are very competitive, commoditized industries. They are particularly dangerous for managers with a flawed understanding of their business: catastrophic mistakes made today may not be revealed for several years, and during the interim, management will double down on their failed strategies. Finance and insurance would be a major part of GE’s downfall in the 2000s: the economics of the finance businesses would be permanently impaired following the 2008 financial crises, and GE eventually took a $15 billion bath on the insurance business.

For the majority of Welch’s tenure, earnings smoothing didn’t even get Welch the high multiple he desired. Cohan notes that in the late 80s and early 90s, a decade into Welch’s twenty-year reign, GE’s stock struggled in the face of investor skepticism about its foray into finance and aggressive acquisition strategy.

Welch and his successor battled critics all along the way, people who simply pointed out the obvious, that Welch’s approach to business was completely backwards. GE faced attacks from short-sellers in the early 90s, and in 1994 the WSJ ran a front-page story about GE’s approach to smoothing earnings. In 1998, SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt made a speech entitled The Numbers Game, where he decried the GE approach of managing earnings (without naming GE specifically), which Fortune writer Carol Loomis followed up on with a feature on earnings management (naming GE) and a report on the trend of blue chip companies setting impossible long-term EPS growth targets (15% per annum was the standard goal at the time, i.e. a doubling every five years). In 2002, bond king Bill Gross criticized GE for its opaque disclosure and heavy reliance on short term debt and leverage (which would bite GE six years later), and in the same year, Congress finally passed Sarbanes-Oxley, which tightened accounting rules and enforcement.

In hindsight, Welch owed much of his success to a unique confluence of external forces that lifted GE’s businesses in the 1980s and 1990s — limited financial regulation, an unprecedented bull market, and a one-time boom in gas-fired power plants — which was more than enough to offset that damage wrought by his management approach. His successor would not be so lucky.

Taking all of this into account, it might be better to invert our earlier question, and instead ask: what made Welch’s philosophy so irresistible to other executives?

Contrary to popular belief, Jack Welch didn’t invent earnings management, or even popularize it. Managers have been smoothing reported earnings as long as companies have been issuing regular income statements. In More Than a Numbers Game, Thomas King cites a 1912 editorial in the Journal of Accountancy stating that managers had been playing games with depreciation to even out earnings, taking higher charges in fat years and smaller charges in lean years. (This was before modern accounting rules standardized depreciation.)

King then describes the curious history of the LIFO tax break. Beginning in 1939, Congress allowed companies to use the LIFO (last-in, first-out) inventory method to calculate earnings for tax purposes, as long as the same method to report earnings to shareholders. This was a generous tax break for any company that cared to take it — the LIFO method would create lower reported earnings, particularly during periods of high inflation (like the 1960s and 1970s), and lower reported earnings translate directly to lower cash taxes. LIFO adoption should have been almost universal in any industry with inventories and rising input costs — in 1981, GE reported that LIFO had saved it $1 billion in taxes to date — but remarkably, many companies declined to adopt it, instead choosing to report higher accounting earnings to investors and pay extra tax.

This curious behavior with regard to LIFO was no anomaly. King also cites a 1983 article by Arthur Wyatt, a partner at Arthur Andersen, recounting the many contortions his clients had gone through to report higher, smoother earnings — ignoring LIFO, currency hedging, off-balance sheet borrowing, and favorable acquisition accounting treatments — none of which created value for shareholders, and most of which actually cost money. And for what? Wyatt observed that under the (then-)newfangled efficient markets hypothesis, none of this window dressing should make any difference to investors. Sure enough, empirical research at the time was already finding that markets are very good at seeing through these types of accounting games, something Welch would soon discover for himself firsthand.

Managers were receptive to Welch’s philosophy because it aligned with what they already believed. They had long accepted as self-evident that it was important to manipulate reported earnings, and Welch’s approach at GE was simply a new variation on an old theme. Other executives listened to what Welch had to say, and what they heard resonated with them — they found Welch to be insightful and profound.

Here is what Warren Buffett wrote in 1988:

[T]he heads of many companies are not skilled in capital allocation. Their inadequacy is not surprising. Most bosses rise to the top because they have excelled in an area such as marketing, production, engineering, administration or, sometimes, institutional politics.

Once they become CEOs, they face new responsibilities. They now must make capital allocation decisions, a critical job that they may have never tackled and that is not easily mastered. To stretch the point, it's as if the final step for a highly-talented musician was not to perform at Carnegie Hall but, instead, to be named Chairman of the Federal Reserve.

It is not useful to think of CEOs as being “good at business” any more than it is useful to think of ballplayers as being “good at baseball”. Baseball skill consists of many different dimensions — hitting, fielding, pitching, etc. — and different players succeed by combining these skillsets in different ways. We see lumbering sluggers that struggle in the field and spry shortstops that are little threat at the plate. Similarly, business skill has many different dimensions — sales, engineering, capital allocation, etc. — and even the most successful executives excel at no more than a few of them.

Big corporations gain tremendous efficiency from specialization, which allows employees to be highly productive without having to understand or excel in every aspect of the business. A star employee of a packaged food conglomerate might start his career as a junior marketer working on a small brand, and over the years develop his marketing skills and management skills and knowledge of the food industry to the point where he becomes Chief Marketing Officer of the entire company.

As Buffett observed, most companies pick their CEOs from a pool of these super-successful specialized middle managers: perhaps the Chief Marketing Officer, or the Chief Financial Officer, or even the General Counsel. These are invariably high-caliber people, but they have been selected for their expertise and experience in a narrow area (and probably some talent for storytelling and self-promotion). When they are promoted to CEO, they find themselves in charge of a lot of crucial areas they have no experience with, like capital allocation, investor relations, financial reporting, and overall corporate strategy.

Imagine yourself in this situation, deciding what to do about investor relations, a field that you have no experience in whatsoever. Your first inclination is that investor relations looks like a marketing problem. You know all about marketing, even if that is not your specific area of expertise. You got promoted by marketing yourself, telling a good story and putting your accomplishments in the best possible light. Your company probably does the same when marketing their products to consumers. You conclude that your company’s stock is just another product to be marketed, and you just need to figure out what kind of messaging will trick investors into giving you a high stock price. At that point you start devoting brain cycles to sandbagged earnings targets, smoothed and/or inflated earnings, and adjusted EBITDA.

None of this will work at all because the whole theory is based on a false analogy: reporting to investors is nothing like marketing to your boss or to consumers. The stock market may not be perfectly efficient, but it is incredibly naive to imagine that it will be fooled by any of these simple gimmicks. You can sandbag your earnings targets, but investors will still benchmark you against your peers. You can inflate reported earnings through addbacks, but it’s easy for investors to identify them and just subtract them back out.

The thing is, CEOs get trapped in that backwards paradigm, because the evidence and logic that disproves it is so counterintuitive. CEOs will argue that they’ve met their investors and know that they aren’t that smart, and won’t listen to any explanation of why the wisdom of the crowd makes that irrelevant. They will point to companies whose stock prices crash after missing earnings by a penny, but they fail to think about it through the lens of rational expectations: if a company is known to pull out every legal trick in the books to meet quarterly earnings targets, then the market will realize that an earnings miss by even a penny is a crucial signal that something has gone seriously wrong inside that company (as was the case when GE finally missed earnings in early 2008).8

Here we should acknowledge: Not All CEOs. We previously looked at David Cote, who understood all of this stuff correctly, and who after being pushed out of GE went on to great success running Honeywell. But for every Cote there are a dozen Welch disciples who get all of this completely backwards and refuse to consider any arguments to the contrary.

American corporate structure has evolved to compensate for this specialization problem. The Man Who Broke Capitalism implies that Jack Welch and GE was the harbinger of the modern approach to business, but in truth, it was the last gasp of an obsolete approach, the 1960s-style diversified conglomerate. GE failed in the same way all of its peer conglomerates failed, extending into industries it didn’t understand. For example, GE’s longtime rival in the electrical equipment space was Westinghouse, which collapsed in the early 1990s after making billions in bad loans to real-estate developers. Even before GE started to collapse, its antiquated structure was being lampooned on 30 Rock: Alec Baldwin played GE’s Vice President of East Coast Television and Microwave Oven Programming.9

Companies today are more focused, and CEOs today are more constrained. Long gone are the days when a department store could jump into insurance or NBC could start renting out cars. Today it’s capital allocation by formula, no transformative M&A, and one false move will have activist investors at your throat. Even if a CEO is working from a backwards paradigm, it doesn’t matter, because his job isn’t to set a bold new corporate strategy, it is to produce and market widgets and mail the profits back to investors. Perhaps the modern CEO chafes at being treated like a super-middle manager, but at least the pay isn’t half bad.

Pop-econ books like The Man Who Broke Capitalism and Welchian approaches to management and reporting are two examples of the same common phenomenon: smart people who become seduced by an intuitive-but-backwards framework, and are inspired go forth writing books and making speeches confidently asserting that wet streets cause rain. Because the framework is so intuitive, they quickly find an audience, and that feedback loop eventually inspires self-destructive behavior from anyone unfortunate enough to be inspired to put theory into action. In a sense, The Man Who Broke Capitalism ends up the perfect book for understanding Jack Welch and GE — if you can understand why smart people fall for that book, then by analogy, you can figure out why smart people fell for Jack Welch. At that point, you can go one step further, and understand why so many smart people support the self-destructive economic policies being promulgated today.

Perhaps this is just a hazard of selecting our CEOs and journalists and political leaders more for their storytelling ability and self-confidence than for their expertise or correct knowledge of how things actually work. (Not to knock storytelling and self-confidence as assets, but they tend to magnify output rather than supply any intrinsic utility themselves. Storytelling and self-confidence in the service of bad ideas are what produce GE- and tariff-scale disasters.) In any case, we can try to “name it and tame it”; if we learn to identify these popular “wet streets cause rain” frameworks, we can better resist them.

The BLS tracks total employment by sector, which includes all kinds of workers within that sector, from managers to assembly line workers. It is also true that the proportion of blue collar workers in manufacturing has declined a bit: Stephen J. Rose of the Urban Institute runs the numbers and finds that blue collar workers made up 70% of manufacturing employment in 1960 and 53% in 2015.

The outcomes actually differ slightly because of taxes: currently, buybacks slightly disadvantage tax-deferred or tax-exempt investors (like those of us who own stocks in our 401ks and IRAs) because companies pay a small tax on buybacks, but they advantage taxable investors who would have to pay income taxes today on the dividends they would otherwise receive.

In Straight from the Gut, Jack Welch claims that in the first 5 years of his tenure (1981-1985), when he became known as “Neutron Jack”, he ended up cutting 19% of his payroll via terminations, and another 9% went to the buyers of businesses they sold – not too far from the recent trend for Unilever and Paypal.

When inflation rises, the President is usually pressured to respond by jawboning individual industries, demanding that they hold the line on prices and wages. Every President between JFK and Jimmy Carter did it, in response to stubbornly high inflation in the 60s and 70s, and Biden even took a stab when inflation recently returned. This strategy is useless because it misunderstands the role of prices in the economy (to ration scarce resources, and to signal shortages and gluts and incentivize market participants to do something about them), and ignores the root cause of inflation, which is overly loose fiscal and monetary policy that reduces the value of the dollar. If you force the steel industry to forgo wage and price hikes, it just ends up out of sync with the rest of the economy; workers will depart for the industries that are allowed to raise wages and underpriced steel will be in short supply, and they will have to raise wages and prices even more in future years to catch up. Jawboning isn’t even the dumbest way that politicians respond to inflation: Nixon instituted wage and price controls and Ford had a whole anti-inflation marketing campaign, complete with buttons exhorting citizens to “Whip Inflation Now” (WIN). Ultimately, inflation was whipped by attacking the root cause: Paul Volcker aggressively tightened monetary policy in 1981, which led to 20% interest rates and a deep recession that contributed to the struggles of Detroit in 1982 discussed in this article, but did succeed in breaking inflation for good.

Even Donald Trump doesn’t think he can affect manufacturing employment by yelling at CEOs – he goes straight to tariffs. Tariffs are also idiotic, but in a totally different way – they create a small handful of low wage jobs at extravagant expense to consumers (i.e., other workers), and destroy productivity and jobs at businesses that consume tariffed inputs.

There is also an extensive literature on growing income inequality; here is an article that does a good job of summarizing the main points. There certainly is an argument to be made that changing cultural norms and the decline of unions have something to do with greater income inequality, an argument that has been made by many in recent years, including Paul Krugman. That being said, the idea that we have to revive blue collar manufacturing jobs to raise incomes for the middle class is cargo cult reasoning — Krugman himself makes the point that there is no reason for unionization to be specifically tied to blue collar manufacturing.

In the last edition, we talked about the success Sam Zell had buying railcars at a discount to replacement cost in the 1980s. GE bought his railcars in the early 90s at a fuller valuation, as a part of its drive to build up GE Capital.

This last point comes from More than a Numbers Game, citing a 2003 article by AEI’s Peter Wallison. Wallison suggested requiring disclosure of what he calls “value drivers”, but what we more commonly call KPIs: CAC, employee retention, and so on. This is a good idea that’s probably worth revisiting.

While pulling up the YouTube link just now, I learned that the GE Trivection Oven was a real product.

It’s very hard to argue with most of this—directionally, companies/CEOs are sub-optimized towards good products or profit. Personally, I’m interested in what you think going forward from this. Specifically, questioning the idea that investors will or even want to suss out bad long term business and, relatedly, given zirp or post-zirp. More broadly, there are many reasons to think of the line being much blurrier between C-suite and investors than we’re giving credit for. The CEO is much more on team investor than team company (with their employees), incentive-wise and even socially. Perhaps you view public companies vs startups as meaningfully different for the point you’re making, could be. But there are many many companies making and selling things very unprofitably explicitly to get an exit before ever having to solve or deal with getting in the black. This is Plan A or a very desirable Plan B . Even public companies have any number of champions for an argument of short term stock price mattering to investors more than long term sustainability (Tesla, GameStop, etc). Maybe those examples feel too trifling, but I’m not sure why we should default expect investors to be long term oriented. Even if the companies eventually make good a decade or two from now, the investors would almost certainly have done better to just jump between the short term wins. You could argue they don’t have the intel to do this well—though this is easier when the execs and investors are “aligned”—but that wouldn’t explain choices of buying into stocks with distorted PE ratios.

You’re right on about questioning who or why leaders become leaders I think. But I’m not sure I agree that their “weaknesses” aren’t actually helping them. They seem to do quite well. Often even when their companies “fail.”

I wrote a review of Thomas Boyle's book: https://enterprisevalue.substack.com/p/foreseeing-ges-fall