The Midwit Trap

Why are we so dismissive of simple solutions?

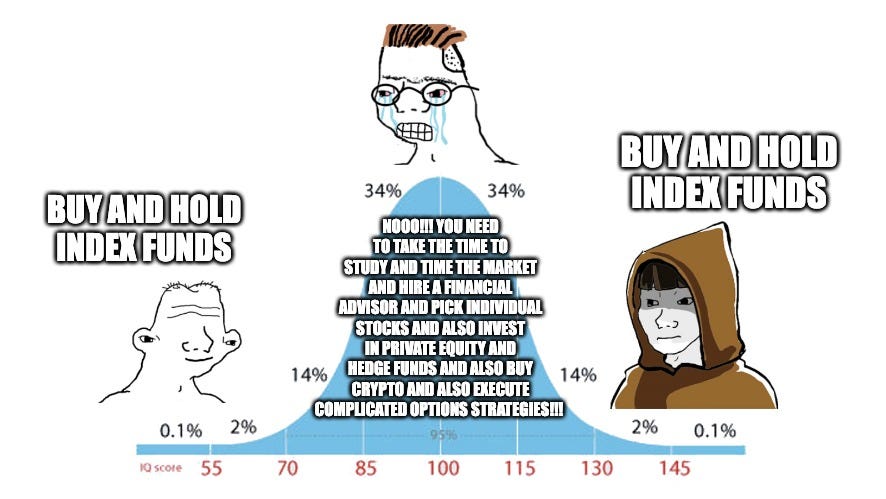

If you spend too much time on the internet, you are likely familiar with the Midwit Meme:

According to Know Your Meme, “midwit” is a derogatory term used to describe someone of average intelligence who mistakenly believes they are among the intellectual elite.

The Midwit Meme is usually used to defend a position that seems too simple and unsophisticated to be correct.

The idea behind the Midwit Meme is that sometimes the correct solution to a complicated problem turns out to be very simple. In this scenario, the genius and the simpleton will both end up with the right answer for very different reasons: the genius will fully understand and correctly solve the problem, while the simpleton will blunder into the right answer for the wrong reasons. (The simpleton always picks the simple answer whether it is right or wrong, an approach that will sometimes lead to the right answer by chance).

It is only the midwit who manages to get the answer wrong, by coming up with a complicated solution that appears smart and sophisticated but ultimately proves to be incorrect.

In the example above, the genius works out that simple index funds are the best solution for most people because the management fees and trading costs associated with most active investing strategies are very high, and end up being the dominant factor in determining returns for most people. The passive investor will generate average returns without incurring any meaningful costs, while active investors considered as a whole must still generate average returns and after that still must contend with high management and trading costs.

The simpleton doesn’t understand any of this but just goes with the default 401(k) index funds and ends up in the same place.

It is only the midwit that believes that all smart people should pursue high-fee active investing strategies, and as a result the midwits (as a whole) are the only ones that underperform.

To be sure, the midwit meme is not remotely true as a rule. Some problems have simple solutions, and other problems have complex solutions. For example, what is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter?

See, it doesn’t work. You can’t just default to the simple answer as a rule.

However, the Midwit Meme does seem to pop up a lot in finance and economics, because there, complicated problems do often have simple solutions (or at a minimum, a simple optimal course of action). This runs counter to our intuition, which is that a complicated problem must have an equally complicated optimal course of action. People are often reflexively dismissive of simple approaches, like index funds.

The Midwit Meme has actually been an unintentional theme here to date; in fact, one could say that this newsletter has been an exercise in writing 5,000 word essays that could have been simple memes.

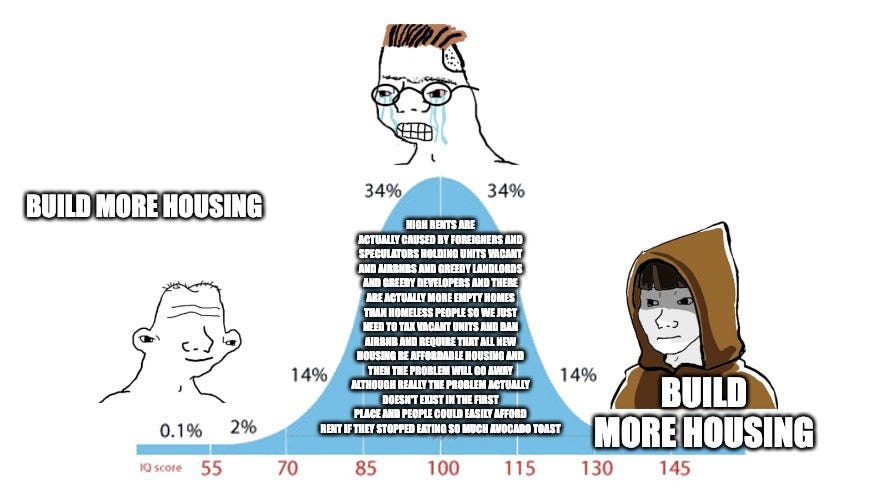

For example, we looked at solutions to the housing shortage:

We examined the sustainability of ride-hailing:

And we studied the fall of General Electric:

You get the idea. The formula for an interesting post is to examine a problem where conventional midwit wisdom would suggest a very complicated solution, and show that in fact the best approach is relatively straightforward and simple. This begs the question: why do smart people fall into the Midwit Trap?

Complex != Smart

There is a famous scene from The Simpsons:

Immigration Examiner: All right, here's your last question. What was the cause of the Civil War?

Apu: Actually, there were numerous causes. Aside from the obvious schism between the abolitionists and the anti-abolitionists, there were economic factors, both domestic and inter...

Immigration Examiner: Wait, wait... just say slavery.

Apu: Slavery it is, sir.

The way we learn about a subject like the Civil War in school is to receive the sanitized, simple outline when we are very young, only to have the true detail and complexity revealed to us as we revisit the subject in later years.

There is nothing wrong with this approach, but it incorrectly implies that every simple explanation in life is a lie taught to us in elementary school, and that we will only understand the truth when we study the subject in detail in graduate school and can write a 60 page dissertation covering every facet.

Since we assume that simple answers are for children, we mock those who offer a simple explanation for a very complicated topic. We laugh at the scene with Apu, but the consensus among those who have studied it in depth seems to be that the Civil War indeed was caused by slavery.

Or, if you prefer:

If one argues that the high rents are mostly the result of laws that prohibit housing construction, they will be met with condescension and mockery. “Oh, dear, you don’t understand, housing is much more complex than that.” “Oh, that’s just what you learned in Econ 101.”

This applies equally to all of our other examples as well. GE pitched their accounting shenanigans as 4-D chess necessary to appease investors and build confidence. Wall Street has always sold complex (high-fee) products as being tailored for “sophisticated” wealthy people and institutions. The case against ride-hailing apps is hundreds of pages of circular “analysis” that deploys fancy financial terminology to obfuscate the lack of substance.

We assume that a complex solution is likely to be the product of more sophisticated and nuanced reasoning than a simple solution, and thus more likely to be correct. This is far from true. In fact, in all of our examples, the complex solution is the result of less sophisticated and nuanced reasoning than the simple solution.

In our housing example, the proposed Rube Goldberg solutions are ineffective because they ignore the economic forces that pull people toward big cities in a modern economy; agglomeration effects literally make people who move to big cities richer and more productive, and therefore only by building enough housing to allow people to move can we hope to achieve progressive goals. The GE strategy of fudging the numbers ignored the simple truth that “you make what you measure”. And so on.

If we accept that a “midwit” is a real type of person, then it is the midwit that will be most vulnerable to this particular logical fallacy, because it targets their insecurity about their intelligence and because they will fail to recognize it. An intelligent person will know that there is no correlation between the simplicity of a solution and the sophistication of the reasoning that led to it (or if anything, there is an inverse correlation).

The Pareto Principle

The Pareto principle is better known as the 80/20 rule: in many cases, a good rule of thumb is to assume that 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes. The classic example is to look at economic aggregates: 20% of the population of a country usually accounts for about 80% of taxes paid, or 80% of wealth.

Some version of the Pareto principle pops up everywhere there is a power law distribution, and power law distributions are far more common than anyone intuitively thinks, at least in business and economics.

In venture capital, a tiny handful of investments account for most of the return, or in gaming, a few “whales” account for most of the profits. Wikipedia has a more thorough list of examples of the Pareto principle; notice that most of them come from business and economics.

The corollary to the Pareto principle is that you can address most of the consequences of a problem by focusing on a tiny number of causes, or maybe even a single cause. Consider our investment management example: management fees are such a dominant factor in determining total return that it is sufficient for most to just focus on minimizing fees while maintaining diversification and to ignore everything else.

In business, one usually gathers data to identify which causes are creating most of the consequences, taking advantage of the Pareto principle to focus one’s limited resources on addressing the main sources of the problem while ignoring the rest for now. Outside the office, people have difficulty maintaining this habit.

The other challenge with the Pareto principle is that the less significant causes continue to exist, even if the consequences are too small to be meaningful. This, in turn, gets people hung up on the logic – how can we acknowledge that a cause exists, and then proceed to just ignore it?

We can illustrate the problem with some napkin math on housing construction. (Note that this is purely illustrative and not meant to be fully logically coherent.)

Housing skeptics will often accuse supporters of housing construction of ignoring other solutions, like prohibiting Airbnbs and taxing vacant homes. So, let’s look at the data. Housing construction in the 2010s was 6.5 million units lower than it was in the 2000s. Meanwhile, there are 660,000 Airbnbs in the US. Vacancy rates have actually been declining, but let’s be generous and say that vacancy taxes can increase national supply by 0.3%, or 500,000 units, about what other cities have achieved.

In this crude analysis, the causes break down 85 / 8 / 7. (Also, this breakdown is very generous, because the underlying logic is incorrect; construction can always be high enough to entirely offset other factors, so you could argue the causes are really 100 / 0 / 0.)

The typical midwit rhetorical strategy is to present all of the causes without also presenting which causes account for what share of the consequences, falsely implying that all causes are equally important. Consider a statement like: “Airbnbs and speculators are among the causes of high rents.” This is a technically true statement, but presented in a way that is intended to lead the reader to a false conclusion, such as “Shark attacks are a growing cause of death in Maine.”

The fallacy here is easy to identify if we transfer our housing example to an office setting. If you were tasked with analyzing customer service issues for a client, and you presented the issues without also showing how common each issue was, you would be fired. If you showed that the issues broke down to an 85 / 8 / 7 ratio, and you still insisted they were all equally important, again, you would be looking for a new job.

It is not clear what the main culprit is here. It could be motivated reasoning, or it could be that we do not encounter the Pareto principle much in our everyday lives and fail to look for it. Nevertheless, failure to recognize the pervasiveness of the Pareto principle is a common factor in incorrectly rejecting simple solutions to complicated problems.

Theory of Constraints

In business, where specialization is critical to achieving efficiency, you see a lot of assembly lines and supply chains. One critical feature of a chain is that it is only as good as its weakest link. This was illustrated during the pandemic, when automotive production was temporarily shut down for a lack of inexpensive computer chips.

For such a system, total output is always dictated by the biggest bottleneck at any given time. You can only increase output by addressing the specific bottleneck that is constraining the whole system at any given time. In our car example, you cannot increase production by increasing the supply of steering wheels or tires; the only thing that will help is more computer chips. Once you have enough computer chips, then something else will be the limiting reagent.

In manufacturing, this is known as the Theory of Constraints. Popular books such as The Goal (for manufacturing) and The Unicorn Project (for software) have been written to show how common it is in the business world, and how to solve the problems it poses. We don’t encounter this issue as much in our everyday lives because we usually have access to lots of substitutes; if the road we usually take to work is closed, we can take an alternate route.

This is not a factor in any of our chosen examples, but this is an issue that confounded people during the pandemic, when shortages abounded. It is not intuitive that a small percentage of the workforce calling out sick will cause major production disruptions, but it is a predictable result of the world being designed around supply chains with limited redundancy.

The Theory of Constraints is a good example of how we are surrounded by complicated systems where the optimal strategy, by definition, is always a simple one: in this case, attack the biggest constraint.

The Divide by Zero Problem

Here is a version of a classic math puzzle:

a = b

ab = a²

ab - b² = a² - b²

b(a - b) = (a + b)(a - b)

b = a + b

b = 2b

1 = 2

Every step of this seems correct at first glance. And yet, it doesn’t seem right that 1 = 2.

The trick is that in the fourth step, you divide both sides by (a - b), and we established in the beginning that a - b = 0. Since you can’t divide by zero, the whole statement is invalid.

Some solutions rely on convoluted chains of logic that are strictly dependent on every single statement being true. They are more likely to have hidden “divide by zero” problems that may be easily noticeable to the experienced practitioner but are invisible to the layman. Simple solutions might have errors too, but they will be much more obvious. Also, complicated chains of logic “feel” correct because a lot of the steps will be verifiably true; people sometimes forget that all of the steps have to be true for the entire argument to have any truth.

In our GE example, management believed that relying on accounting tricks to impress investors would lower their cost of debt and raise the stock price which in turn would improve their ability to attract good employees and make acquisitions which would then lead to a positive feedback loop that would eventually increase real world profits. This is an impressive solution on paper but ignored the simple fact that managers rely on accurate accounting to get the feedback they need to successfully run a business! It did not end well for GE.

Complicated stories seem more likely to be logically sound to a midwit, but simple strategies are actually far less likely to have hidden land mines.

We Share 99% of our DNA with Chimpanzees

In business, as in biology, sometimes it is just the 1% that is different that matters, and you can ignore the 99% that is the same. It doesn’t matter if we share 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees, because the difference is all in the 1%.

Successful entrants often only change a tiny percentage of the business model. Netflix produces video entertainment in much the same way as cable networks did for decades, it’s just that

they deliver it on-demand over the internet. Still, an on-demand model is better than scheduled linear programming across every dimension, so we have mostly shifted our consumption of scripted entertainment from linear cable networks to on-demand streaming providers.

This phenomenon is everywhere. New airplane models and engines might differ from the old ones by slightly improving capacity and fuel efficiency, and are otherwise identical; still, that is often enough to render the old models fully obsolete.

Note that this only holds if the 99% is actually the same. Many (if not most) new technologies are worse across some important dimensions. Planes are fast and fuel efficient but are only suitable for longer trips because they require going to an airport, enduring a long boarding and takeoff process, and then doing the reverse on the other end. Despite being slower and more expensive on a per-mile basis, trains are better for shorter trips because they are quick to board and leave and you start and end at stations in the city.

Nevertheless, people get hung up on the idea that two products need to be drastically different to generate meaningfully different outcomes. If a new product is 99% similar to an existing product X, people immediately exclaim: “X. You invented X.”

In our ride-hailing example, skeptics make much of the fact that ride-hailing is mostly the same as taxis, and devote much attention to proving this; they both use drivers, cars, fuel, etc. The difference is in using software to manage dispatch and improve the user experience. No one denies the other 99% is the same; in fact, that is a key selling point!

Again, the incorrect heuristic here is to assume that making a small change in one part of a complicated system cannot have a huge impact on the output. How can restricting construction in a few cities drive up rents nationwide? How can reducing management and trading costs have such a big impact on total return? Once you understand that a small change can have an outsized impact, it is easy to see that a simple solution will often be more effective than a complex one.

In Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb introduced the idea of Mediocristan and Extremistan. In Mediocristan, everything is normally distributed, and extreme events rarely happen. In Extremistan, there is an exponential distribution and extreme events happen much more often.

The Midwit Trap is to some extent just an application of Extremistan. The effectiveness of a simple solution depends on having a problem where one cause is responsible for most or all of the negative consequences. This is likely to be the case where there is a power law distribution or strict dependencies, but not so much elsewhere. We are used to solving problems in Mediocristan, where we usually cannot achieve a significant outcome with “one simple trick!” and so we are dismissive of simple solutions or simple explanations.

The Midwit Meme turns out to have a useful purpose, to remind us in a concise, memorable way that we cannot accept complicated solutions or explanations only because they feel smarter than a simple solution.

Midwits can form consensus reality bubbles that last for years. This is how politics online 2016-2022 has functioned, with so much airtime given to denialism about whether or not a boomer reality tv star was in fact the figurehead of a fascistic movement.

I think the pi meme is actually correct. In physics we usually approximate it as 3. (Although I've seen quantum/particle physics professors approximate it as 1 LOL)