Stock Buybacks, Demystified

Everything you wanted to know about stock repurchases but didn’t care to ask

Around this time last year, the New York Times Guild (the union that represents NYT newsroom employees, among others) was in the middle of a particularly contentious contract battle with NYT management that had dragged on for multiple years. The Guild publicly expressed frustration over stagnant wages and shrinking pension benefits at The Gray Lady, common worker grievances.

There was one particularly interesting talking point the Times Guild returned to and hammered on repeatedly: the NYT’s stock buyback program. Almost every Guild press release and tweet during this period expressed outrage over the NYT’s share repurchase policy. The Guild characterized the NYT’s repurchase program as “egregious” and an “insult”.

One curious thing about the Guild’s anger over the NYT’s supposedly egregious and insulting repurchase policy is that over the preceding three years, the NYT had in fact hardly bought back any of its own stock!

The NYT’s 2022 annual report reveals that the company had made nearly $500 million in net income over the last three years while spending only $105 million on share repurchases. And most of that $105 million simply went to offset the $72 million of stock-based compensation issued over that time. (Stock-based compensation represents the value of newly issued restricted stock or stock options given to employees in lieu of cash, while buybacks represent the reverse, cash given to investors for stock which is then retired. Any buyback program should therefore be measured net of stock issued.)

The NYT’s net stock buyback over that timeframe would therefore have been only $33 million (ignoring some minor tax and option adjustments), or only 7% of net income earned over the preceding three years. By comparison, the members of the S&P 500 (an index whose constituents make up the majority of corporate profit in America) spent 44% of their net income on buybacks last year.

If the Guild wanted to be mad about the NYT’s choice to give cash to shareholders, they could have focused their ire on the NYT’s generous dividend, which totaled over $140 million over that period. Or they could have protested the NYT’s acquisition of The Athletic in 2022, which saw over $500 million of the NYT’s cash distributed to shareholders of a different company. But no, it was Times’ meager buyback that set off the Guild.

Something specifically about stock buybacks seems to trigger strong emotions: to most, buybacks intuitively seem frivolous, manipulative, and wasteful. Critics blame buybacks for a wide variety of societal ills, from inequality to low productivity. Last year, Congress passed a 1% excise tax on stock buybacks, with the Treasury Department stating that “as the tax code has favored stock buybacks, many companies have failed to reinvest profits in their workers, growth, and innovation.”

But if you ask financial experts, the fuss around buybacks is much ado about nothing. Morgan Stanley analyst Michael Mauboussin says that buybacks are important and misunderstood, and AQR founder Cliff Asness dismisses buyback criticisms as symptoms of “Buyback Derangement Syndrome”. And here is what Warren Buffett had to say about repurchases in last year’s Berkshire Hathaway annual letter:

When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).

So, do buyback critics have a point, or are they a bunch of economic illiterates?

First, let’s start with a story.

You have a job at the local widget factory, and you are living a happy life. You collect a wage and spend it on cheeseburgers and beer. One day it occurs to you that you will one day want to retire and be able to eat cheeseburgers and drink beer without having to work every day at the widget factory.

The next logical step here would be to set aside some of your wages in a savings account, but in our story, savings accounts haven’t been invented yet. You have to find some other way to defer consumption.1

You decide that you will enact your savings plan by launching a successful newspaper. Like, a real, old school, print newspaper, just like the original New York Times. Your plan is to cut back on the cheeseburgers and beer, and use the money you save to buy a printing press and ink and hire journalists and pressmen.2 If people like your newspaper, they will exchange their hard earned dollars for your newspaper, and advertisers will supplement this with even more dollars to reach your readers.

Most of the dollars you receive will go right back out the door to produce the newspaper — to buy paper and ink and to pay the journalists and pressmen — but the leftover dollars, your profit, will be enough for you to buy cheeseburgers and beer until you die.

We can use this little sketch to understand how private investment affects the economy. In the first part of the story, you contribute to the production of goods and services through your job at the widget factory, and in exchange you receive pieces of paper that you trade for goods and services that others produce (cheeseburgers and beer).

In the second part of the story, you choose to buy fewer cheeseburgers and less beer, and use your money to buy printing presses and journalists instead. You are reallocating society’s scarce resources (labor and land), nudging society to grow fewer hops and raise fewer cows and instead mine metal and craft it into advanced machinery. Fewer farmers, more miners and craftsmen and journalists.

On a societal level, a successful newspaper is a good trade for everyone involved. Consumers like your newspaper enough to vote for it with their pocketbooks. Workers like your newspaper enough to vote for it with their feet. And you make enough profit to fund your retirement.

You can see the accounting behind an unsuccessful newspaper as well. Consumers don’t vote with their pocketbooks, workers don’t vote with their feet, and after your newspaper shuts down, society’s scarce productive resources will be redirected elsewhere to produce something people actually want, perhaps to back to grow more hops and raise more cows.

There are certainly other important impacts on society from your newspaper that are not captured by economic success or failure: perhaps your newspaper’s coverage creates a more well-informed electorate (good!), or maybe your newspaper disseminates misinformation that sows confusion and division among the masses (less good!). But we will set these externalities aside for now, focused as we are on the narrow issue of stock buybacks.

Successful ventures create economic growth by allowing society to produce more and better output with the same scarce inputs. That’s the name of the game: society is working with a (relatively) fixed pool of labor, land, and natural resources, and we have to figure how best to turn that into useful economic outputs.

Now, you are probably wondering what this all has to do with stock buybacks. Well, we can select individual features of a modern economy to layer onto our simple model, like so:

A business can be launched as a sole proprietorship, where there is no separation between the owner and the company. However, in reality, any significant business venture usually is formed as some kind of limited liability partnership or corporation. Effectively, you take your newspaper, and, as SBF might put it, you drop it into a kind of invisible box.

The box is not real in a physical sense, but it is very real in a legal sense. The box has a lot of useful features: it can enter into contracts, it can sue or be sued, it limits liability to its owner(s), and economic claims on the box can be sliced in a myriad of different ways.

Most importantly, nothing about the box changes the economics of the newspaper inside in any meaningful way. The newspaper is just as it was before, and the box simply adds a useful layer of abstraction.

Here is how a modern business venture looks with the addition of the box:

Some promoter comes along and tells you that if you put your money in a magic box today, your money will multiply, and in the future you will be able to take more money out of that box than you put in originally.

The promoter goes and buys ink and printing presses and hires journalists (all inside the magic box), in an effort to make their promises come true.

It worked! The magic box is now spitting out money and rewarding the people who put their money in the box in step 1.

Or, alternatively, it didn’t work, too bad, maybe next time. You diversified your savings across a bunch of different boxes, right?

We need to examine step 3, where the magic box returns money to the original investors. The buyback skeptics would have us believe that it is very important how the magic box spits money back out to the original investors. Our task is to ascertain whether that is the case.

Claim: Stock buybacks are uniquely damaging to society when compared to dividends.

In the olden days, if you raised equity investment to start a company (that is, if you sold off slices of your magic box), and it was successful, your investors would expect to receive ongoing regular cash dividends, to be paid out of profits. They would treat that as reliable income that they could expect to use for their everyday consumption needs, e.g. cheeseburgers and beer.

The proportion of profits used for dividends (the “dividend payout ratio”) would vary by circumstance, but it was typical for that figure to reach 60% to 80%, with the remaining 20%-40% reinvested in the business for future growth — think of a newspaper periodically buying larger, more efficient printing presses.

Edgar Lawrence Smith, in his landmark 1924 study Common Stocks as Long Term Investments, found that stocks had been historically undervalued because investors failed to properly appreciate the value of the “profitable reinvestment…of their undistributed earnings”. Investors in that era mostly just focused on the value of the regular dividend, comparing it to the coupon on comparable bonds. However, that 20%-40% of retained earnings, redeployed in the business, compounded into higher dividends over the years, leaving fixed-coupon bonds in the dust.3

Returning to our model, imagine our newspaper now has a hundred investors, each of whom own 1% of the company. If they are all looking for a steady income far into the future, then dividends work great to satisfy everyone’s consumption needs.

But imagine one of our hundred investors wants to make a big purchase, perhaps one of those newfangled cars. To fund it, they want to sell their share, exchanging their future stream of income for a big pile of money that they can spend today.

One way to solve that is to have a marketplace where they can be matched with a saver who wishes to buy a future stream of income, and make a trade. And as long as there have been stocks, there have been stock exchanges where they can do just that.

Another possibility is for the company to step in and buy that investor’s share on behalf of the remaining investors. This is a stock buyback or repurchase. The company will have to part with a chunk of cash, but at the end of the transaction, the remaining investors will each own a larger piece of the company (1.01%, instead of 1%).

There are a few reasons why this might make sense:

The newspaper’s management team should be better informed than most about their own company’s value. They are well placed to accept a good offer and pass up a bad one.

The group of people in the world that places the highest value on the newspaper is their current investors. Otherwise they wouldn’t be holding the stock! The existing investors are natural buyers for any stock that comes on the market.

The newspaper is generating plenty of excess cash, which it is currently using to pay dividends.

The problem with this plan is that we already established that some of our shareholders are relying on the dividend to pay the bills, so our buyback plan is out. Oh well.

And so it was that in the olden days, buybacks were fairly uncommon. But one can start to see how repurchases could make sense, if conditions were to change in the future.

Now, our shareholders can still use their dividend to buy stock from the selling shareholders, and in fact, if our shareholders all chip in equally to do so, they will be in the exact same economic position that they would have been had we cut our dividend to do the buyback.

Broadly speaking, dividends and buybacks will be the same economically – they are just different ways to get cash from the company into the hands of shareholders. Buybacks initially put all of that cash into the hands of shareholders who want out, while dividends initially distribute the cash equally among all shareholders.

Going back to our history lesson: In the olden days, stock investing was largely the province of a few very wealthy people buying individual stocks for their dividends. In 1900, a single share of stock would typically cost $100 (no fractional shares back then!), at a time when the average annual income was $450. There were only a couple of hundred listed companies of any size, and the largest among them had about 10,000 shareholders.

Gradually, the world of stock investing expanded. Incomes exploded, opening up new demand for long-term saving, and industrial conglomerates like General Electric and U.S. Steel were formed, soaking up that demand. By 1920, the most widely held stock was AT&T, with 130,000 individual shareholders – but that was still only 0.1% of the country’s population.

The Great Depression put a damper on stock investing for a while, but by the 1950s, retail brokerages like Merrill Lynch had pushed down commissions and expanded stock investing to a somewhat wider audience. In 1952, still in the shadow of a brutal post-Depression bear market, an NYSE survey found 6.5 million shareowners in America, representing about 4% of the population at the time. The go-go market of the 1960s would take this figure all the way to 31 million by 1970, which represented 15% of the population, or a quarter of all adults.

The painful bear market of the 1970s would cause stock ownership to actually decline slightly over the next decade. Open market buybacks were difficult to execute under the rules of the time, but companies such as Teledyne and the Washington Post took advantage of the low valuations to launch tender offers to buy back cheap stock, often with spectacular success. Still, buybacks were uncommon, and dividends ruled the day.

In 1982, the SEC passed rule 10b-18, which provided a safe and legal way for companies to execute stock buybacks on the open market, without resorting to tender offers. This is usually falsely cited as the takeoff point for buybacks, because even a full decade later, companies still strongly favored dividends: in 1992, companies spent $94 billion on dividends and only $22 billion on buybacks.

The advent of 401(k) and IRA retirement plans in the early 1980s fueled a boom in stock investing through mutual funds. Only 6% of households were invested in mutual funds in 1980, but that proportion would soar to 52% by 2001. That share of households invested in mutual funds is still about the same today, with the main difference being that low-cost index funds have caught up to actively managed funds. Meanwhile, direct ownership of stock stagnated: today, still only 22% of households own stock outside of their retirement plans.

The popularity of index funds and mutual funds caused a shift from direct retail ownership to institutional ownership of stock (which includes pension funds and mutual funds). Institutional ownership grew from about 30% in 1980 to about 80% today.

Now we have better conditions for buybacks. It is no longer the case that most investors directly buy shares in individual companies in expectation of a reliable passive income. We buy stock via index funds in retirement accounts, with no need for current income, just the expectation that we will cash them out at retirement as needed. We are barely even aware of the dividends we receive, because we automatically reinvest them back into more shares; we have no problem if companies reduce dividends to buy shares on our behalf. Also, if we need cash, it’s now trivial to cash out small slices of our existing holdings with minimal transaction costs.

Buybacks do carry some minor tax advantages over dividends, but the chief advantage is flexibility. In practice, regular dividends are viewed as a commitment, and it is quite a commitment to pay out a dividend of 70% of one’s normalized earnings each and every year. A major recession or an event like Covid can leave a company scrambling for cash.

Most companies find it much better to have a smaller regular dividend, with the balance of excess cash to be returned to shareholders via a flexible buyback policy; many shareholders would have just used the larger dividend to purchase more stock anyway, and so will be completely indifferent.

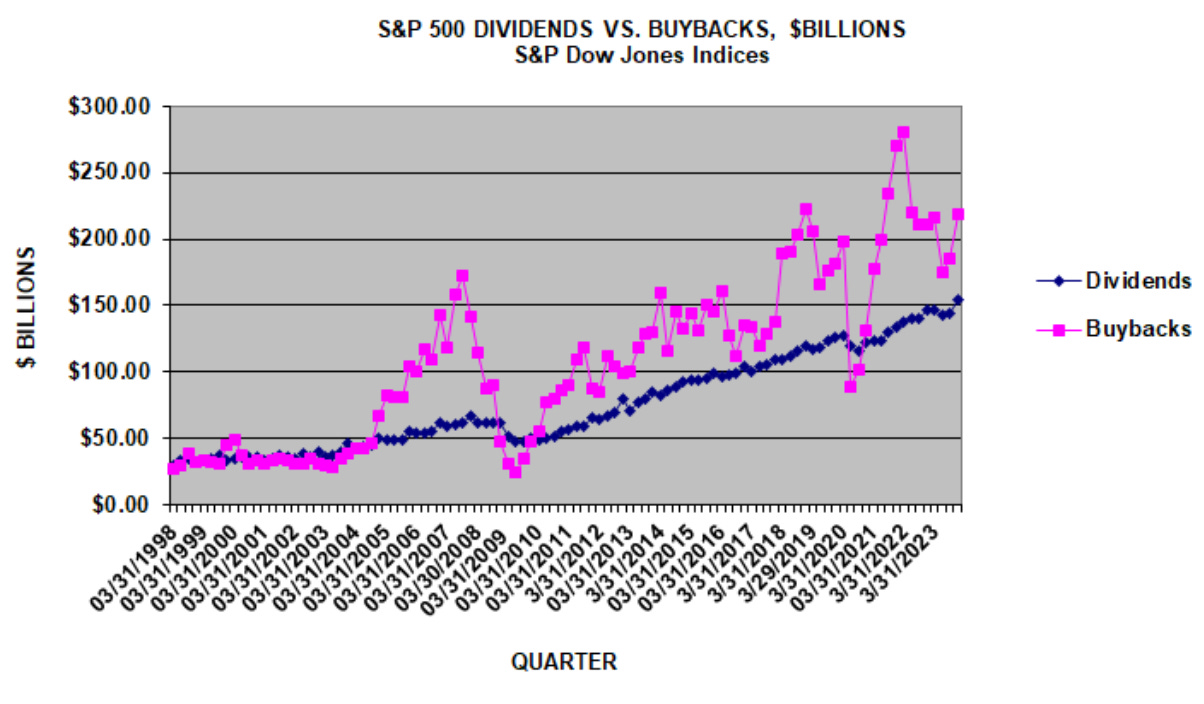

Today, most companies pay a steady small dividend alongside a larger but fluctuating sum of cash that goes toward buybacks. In lean years, many companies omit buybacks entirely, as the NYT did in 2020 and 2021. Here is the S&P’s chart showing how buybacks and dividends over the last 25 years, where we can clearly see that buybacks now well outstrip dividends, except during recessions:

In 2023, the constituents of the S&P 500 earned $1.8 trillion in aggregate, and only paid out a third of those earnings ($588 billion) in the form of dividends. They then paid out another 44% of earnings ($795 billion) in buybacks, for a total payout ratio of 77%. American companies pay out about the same share of their earnings that they did a century ago, a decade ago, or any time in between.4 It’s just that over the last thirty years, the form of that payout has shifted from dividends to buybacks.

When you invest in an S&P 500 index fund in your 401(k), you are buying a slice of a magic box that spits out $1.8 trillion a year in earnings, and that $1.8 trillion will grow in the future as the constituent companies reinvest a small portion of those earnings ($400 billion) on your behalf and as they ride the growth of the global economy. The other $1.4 trillion is distributed to you and your fellow owners to reallocate as they please.

You can create compounding financial returns for yourself by using your share of that $1.4 trillion to buy more shares of the magic box from owners that want out. Ignoring taxes, you are indifferent as to exactly how that happens: you can use your dividends to buy shares from selling investors, or the company can use that money to buy shares from selling investors on your behalf. You will end up in the same place either way.

Claim: Corporations are acting immorally or dishonestly when they buy back stock or pay dividends.

Not only is this claim illiterate, it is in a sense precisely backwards. Remember that the whole game is to induce people to defer consumption and put their money inside a box with the promise that if all goes well, they (or their future designees) will someday be able to take more money out of the box than they put in.

If you are running a company that is throwing off cash, and you don’t have many opportunities for reinvestment, then your investors will say “hey why don’t you give us that cash so we can productively invest it elsewhere”. If you say “haha no”, then a) they will try to fire you if they can and b) you are the one acting immorally. You (or your predecessor) raised money from investors with the promise that they would make money if things went well, and now you are pulling the rug on them.

The ability to return capital is a load-bearing pillar holding up capitalism. People will only put money in a box if they believe they can get it out later. (Insert your favorite joke here about crypto, NFTs, or airlines, but this statement still rounds to being completely true.) If companies can’t or won’t return capital to shareholders, then people won’t invest, and the system falls apart.

One confusing aspect here is that as a society we want capital to flow to the most productive projects, so companies with lots of investment opportunities should be retaining their earnings for investment or even raising new money from investors, while companies with few investment opportunities should be returning every dollar they can. It’s always debatable what any particular company should be doing at any specific point in time. But we always expect some companies to be returning capital to investors and some companies to be raising capital from investors.

Interestingly, people intuitively understand distributions when they start a personal, wholly-owned LLC for some small new consulting venture. No one worries that they are acting immorally by taking a distribution from their LLC; they understand that the LLC’s money is their money, but temporarily held inside a box that they fully own.

If Apple has $160 billion of cash, and you own one share of Apple representing one-sixteen-billionth of the company, then Apple is holding $10 of cash that belongs to you that they will someday choose to return. People intuitively believe that Apple and their personal LLC are economically completely different, but ignoring taxes, they are economically very similar.

Claim: Stock buybacks and dividends are a “waste of money”.

No! Again, this is illiterate. A company that has $100 million on deposit at Chase has an entry in a ledger that Chase maintains that entitles the company to $100 million of goods or services in the future.

Let’s say that the company has ten shareholders that each own 10% of the company, and it decides to distribute that $100 million to those shareholders via a dividend.

What happens now? Chase reduces the company’s ledger balance by $100 million and increases the balance in each of the individual shareholder’s ledgers at Chase by $10 million. That’s it.

The money was inside the box before, and now it is outside the box, but the money always belonged to the shareholders. Money is simply moved from one pocket to another. Nothing is being “wasted”; in fact, economically nothing is really happening at all. No real goods or services are being consumed here, as opposed to our earlier example when scarce labor and capital was being diverted to produce printing presses and journalism.

There is some indirect practical future impact from the money no longer being trapped inside the box; presumably the individual shareholders will use the money differently than the company would have, for better (if the company is constrained in their investment opportunities) or for worse (if the company is passing up high-return investment opportunities to make the distribution). But in no case can a distribution unequivocally be framed as a “waste”. For mature companies, there is usually some positive optimal level of distributions, which is why shareholders are willing to pay taxes to free their money from the box.

A stock buyback is economically more similar to the choice to move cash from a checking account to a money market fund than it is to the purchase of a new printing press.

Claim: Stock buybacks are a vehicle for executives to extract more compensation by artificially inflating stock prices.

The rough intuition behind this claim is the notion that stock prices are determined by supply and demand. The argument goes that stock buybacks increase demand, and therefore stock buybacks must artificially inflate stock prices. Furthermore, since executive pay is tied to stock prices, whether through share and option grants or bonuses, it is argued that executives undertake stock buybacks for selfish reasons, to inflate their own pay.

We have already looked at one problem with this model: increased buybacks have historically been funded by reducing dividends, and savers are likely to reinvest their dividends right back into stocks, just as you do automatically in your 401(k). If we account for the reduction in demand from lower dividends, it’s not clear that there is any meaningful net increase in demand from increasing buybacks.

Even if we ignore that, aggregate buybacks are simply not large enough to have a meaningful impact on stock prices. We can use the S&P 500 to stand in for the entire market of publicly traded companies in America; company value follows a power law and the S&P 500 (which consists of the 500 most valuable companies in the US, more or less) accounts for 80% of total publicly-traded US market value (and in fact over half of all US corporate profits). In 2023, S&P 500 companies bought back 2% of their stock in aggregate. One would not expect that buying only 2% of the stock of a company over the course of an entire year would have any meaningful direct impact on the stock price – investors often build 2% positions in much shorter time periods without any noticeable effect on the price of a stock.

Note that this is true for companies in aggregate, but not necessarily true for any specific company. One can easily imagine a smaller company with a cult following aggressively repurchasing enough stock so that all rational investors sell out, leaving only cult members trading stock amongst themselves at a high price. However, most corporate profits, dividends, and buybacks are concentrated in a small number of very profitable companies at the very top – Apple and Alphabet combined accounted for 18% of all S&P 500 buybacks in 2023, and the top 20 companies combined accounted for nearly half – so activity at smaller companies won’t matter, even in the aggregate.

We have also noted here in the past that one would expect buybacks to shrink executive compensation, all things being equal. Executive compensation is proportional to the size of the company being managed (last year, Tim Cook’s target compensation was seven times that of the CEO of the NYT), and buybacks shrink the value of the company, as they move value outside the box.

The way to grow executive compensation would be to forego buybacks and dividends and instead retain profits to make internal investments or to buy other companies,5 which will cause the company to grow exponentially over time. This indeed was a popular strategy during the conglomerate craze of the 1960s, but this tended to destroy value (or at least transfer value to the shareholders of target companies) so it quickly fell out of favor with investors. Buybacks usually happen because investors like them; most executives feign enthusiasm but merely tolerate them so they don’t get fired.

Finally, some make the more nuanced argument that buybacks can be a trick to inflate the value of stock option packages specifically; the idea is that buybacks shift returns from dividends to capital appreciation, and stock options only gain value with capital appreciation. The problem with this argument is that the effect size would be fairly small, and in any case, options have fallen out of favor over the years, going from 70% of CEO stock comp in 2006 to only 34% in 2022.

Claim: Stock buybacks divert money that would normally go to increase wages, as demonstrated by the fact that wages flatlined at the same time stock buybacks were liberalized, in 1982.

This one is pretty simple. The NYT goes out and sells newspaper subscriptions and ad space for money. The workers at the NYT, who (in conjunction with the NYT’s external suppliers) produce the newspaper, would like to capture as much of that money as possible in the form of wages. The money that is left over after paying suppliers and employees is profit, which goes to the owners. The owners would like to capture as much profit as possible, and they will fight with the workers and suppliers over how the pie is split.

Buybacks and dividends and investments have nothing to do with it. Sure, after they clear their profits, the owners need to figure out how to reinvest their money in the highest return projects possible, and usually this means pulling cash out of the company via buybacks and dividends and investing in new external projects. Sometimes it means leaving profits in the company and investing in internal projects, but it is the nature of successful investment that it simply turns into more money later, so even internal investment must eventually lead to bigger buybacks and dividends, because at some point, internal investment opportunities will get tapped out. (Indeed, the handful of companies that drive a disproportionate share of all buybacks today are always going to be the companies that successfully reinvested retained earnings in the recent past — that list today includes Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta.)

Complaining about high profits and high buybacks and/or dividends is totally redundant and illiterate. It is like complaining that the CEO gets paid too much and he deposits his paycheck into his bank account. Profits have to be returned to the owners eventually, and buybacks and dividends (and sometimes the sale of the entire company) are simply the vehicles through which this happens. Higher buybacks have chiefly come at the expense of lower dividends, but in any case, both happen after the company has booked their profits, so it is highly unlikely that buybacks lower wages.

It is natural that the Times Guild should publicly negotiate for higher wages at the expense of corporate profits – after all, collective bargaining is the point of a union. And in a way, it’s quite clever for a newsroom to employ economically illiterate talking points in service of wage negotiations. What is management going to say? “Don’t listen to our newsroom, they are economically illiterate, also subscribe to the New York Times for only $1 per week and become better informed about the world!” But we should still call out economic illiteracy when we see it.

It is also worth noting here that high corporate profits and buybacks can’t be the source of broad-based lower wages anyway, simply because the most profitable companies are not the largest employers. Corporate profits are largely a function of high productivity and sustainable competitive advantages, and so are not remotely evenly distributed among companies.

In aggregate, the S&P 500 only employs 20% of US workers, despite accounting for over half of all corporate profits. A huge share of American workers are at smaller companies that hardly make any profit at all. There is a huge disparity even within the top of S&P 500: Apple made $97 billion last year despite having only 90,000 US employees, while Wal-Mart made only $16 billion last year with a US workforce of 1,600,000! Even if the most profitable companies decided tomorrow to share more of their profits with their employees, it would do nothing to improve the lot of most workers, simply because the most profitable companies employ such a tiny share of the total American workforce.

As for the final claim about 1982, the claim that real wages have flatlined since the early 1980s has been repeatedly debunked over time, and we already saw that buybacks didn’t gain much traction until well into the 1990s. In any case, corporate profits are unlikely to have been the source of widespread wage pressure, since they have gone up only a couple of percentage points over the last forty years, and even that increase is partially attributable to falling effective corporate tax rates.

Claim: Stock buybacks funded by debt are a harmful form of “financial engineering”.

In our original model, we only have one way of funding capital investment, the sale of equity. You put your money in a box, the managers of the box use your money in some business venture, and if that venture is successful, you get a fixed percentage of all the money thrown off by that venture from now until eternity.

In the real world, we have another popular way of funding capital investment: the sale of debt. This is a slightly different kind of contract. You still put your money in a box, but instead of getting a fixed percentage of all of the money thrown off by the venture for eternity, you get a fixed dollar amount for a fixed period of time (and you also get your fixed dollar investment back at the end).

This is a minor feature to add to our model. Equity and debt are very similar at a fundamental level: you defer consumption today in the hope of more consumption tomorrow. The main difference is in the payoff schedule. The payout for the equity investor is subject to much more variance; the debt investor gets a fixed payout, and the equity investor gets whatever is left over. An entrepreneur will usually raise money using a mix of both equity and debt, depending on the availability and price of each instrument in the market.

You will often see a pundit work himself into a lather over these kinds of basic capital structure decisions, fulminating about how virtuous old-fashioned physical engineering has been displaced by dishonest modern financial engineering. As evidence, he will point to transactions where a company swaps debt for equity, such as a leveraged buyout (in which a sponsor buys out existing equity owners in part with money raised from debt investors) or a stock repurchase funded in part with newly-issued debt. (Curiously, no one complains when companies engage in the opposite form of financial engineering – using retained equity earnings to pay down debt.)

There is nothing inherently good or bad about swapping debt for equity or vice versa, despite the moral connotations often applied to debt generally. Debt and equity have different advantages and drawbacks, depending on the specific situation. We have been funding companies with different mixes of debt and equity for centuries. When you made (or will make) your biggest financial investment – your home – you likely funded (or will fund) that investment with a huge slug of debt and a sliver of equity. This is all perfectly well and good, because your debt payments align with your likely future income stream.

The 2010s were a period of very low interest rates. Naturally, some corporate executives responded to this by issuing cheap debt and using the proceeds to retire expensive equity. For example, Apple had $121 billion of cash and zero debt at the end of fiscal 2012; this shifted to $148 billion of cash and $113 billion of debt by the end of fiscal 2023. Apple borrowed money and used it to buy back stock.

This is fine. Managers are supposed to respond to price signals by giving investors what they want. If investors are willing to pay a dear price for debt (Apple’s average effective pre-tax interest rate on outstanding term debt is less than 3%) and demand a high price for equity, Apple executives can make everyone happier by issuing cheap debt and using the proceeds to redeem expensive equity. Investors get the debt they crave and dispose of the equity they don’t want.

Observe that this is simply a recapitalization – investors as a whole still own Apple in its entirety, just chopped up in a slightly different contractual form. This recapitalization might have been conducted through share repurchases, but it could have been done through dividends instead and ended with the same result.

Nothing immoral occurred here, there was no manipulation, and there was certainly no displacement of physical engineering. This was a good trade for everybody. Within certain limitations around complexity, taxes, and risk, it is desirable that companies respond to changing circumstances and price signals by altering their capital structure, and when they do so, it is inevitable that they will use stock buybacks as a tool.

Claim: Stock buybacks are harmful to society because they discourage investment.

This is the crux of the debate around stock buybacks. The argument here is that stock buybacks displace productive economic investment. The story goes that if businesses would just reinvest their profits rather than give them back to shareholders, society would be much better off.

Let’s think about what would happen if major companies went from retaining 23% of their earnings (as they do today) to retaining 100% of their earnings.

Well, first, big business would get much, much bigger. Companies that reinvest earnings productively will not only grow, they will grow exponentially.

We have seen this historically not only with conglomerates like Berkshire Hathaway, but also capital-intensive juggernauts like Wal-Mart, McDonalds, and Southwest. They started from a few stores (or planes), and each year, they reinvested almost all of their earnings into more stores, and after a couple of decades, they had thousands of stores. Eventually, they saturated their markets, stopped building more stores, and started returning gobs of cash to shareholders.

Last year, the S&P 500 returned $1.4 trillion to shareholders in dividends and repurchases, or 3.5% of its market value. If those companies instead used that money to invest internally year after year, in only twenty years, they would double in size relative to the rest of the economy (relative to the counterfactual), and in twenty more years, they would double again.

However, remember that our other economic inputs, such as labor, are fixed. For existing big business as a whole to grow much faster than the broader economy, it would have to aggressively displace smaller businesses. If the S&P 500 employs 20% of all workers today, imagine what it would mean for that group to quadruple in size.

In our thought experiment, new business formation would be throttled as well: while big incumbents would be newly awash in capital to redeploy, savers would be starved of the cash they would usually use to fund new enterprises.

Historically, startups have been the engine of American growth and innovation, and without them, the corporate landscape would look much different. For example, here is a list of the original Dow Jones Industrial Average components from 1896:

The American Cotton Oil Company

Distilling & Cattle Feeding Co.

North American Company

The American Sugar Refining Company

General Electric Company

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

American Tobacco Company

The Laclede Gas Company

The United States Leather Company

Chicago Gas Light and Coke Company

National Lead Company

United States Rubber Company

In this world, anyone with an innovative business idea would be at the mercy of gatekeepers at existing big businesses, who now would control all the cash. Would we expect a Manager of Corporate Development at The American Cotton Oil Company to spot and oversee the next Google?

We could go on and on with this reductio, but here we should stop and identify some of the errors in the original premise.

For one, the statement “buybacks discourage investment” carries with it an implication that more investment is always better, when in fact the goal is to find the optimal dose of investment for each organization.

Investment consumes scarce societal resources, so it is nonsensical to talk about the risk of discouraging investment without first defining the optimal level of investment and then showing that major companies are falling short of that mark, something that no critic ever does.

This is a general issue with models that appeal to our intuitions. We never have to think of broader economic constraints when we buy a loaf of bread or fill a tank of gas — we just worry about the price and otherwise think of the supply as infinite, which for our purposes it might as well be. But when we model the economy as a whole, we have to think carefully about all of the economic constraints within the system, such as the size of the labor pool – companies can’t just increase investment without disrupting other parts of the system.

Finally, there is a common fallacy at play here, which is the false analogy between a household budget and a corporate budget. In reality, corporate managers do not have the full discretion to reinvest earnings as they please. Investors are worried that managers will squander their cash, and so they expect managers to justify their capital allocation decisions, and they generally expect managers of large, mature companies to return the majority of the cash they generate back to investors.

This works the other way as well: companies are not limited by their retained earnings either. If they can convince investors that they have a lot of good investment opportunities, they simply raise more money from investors to act on them. Smaller companies do this routinely, through the sale of equity and debt. Companies are constrained, but in a much different way than households are.

Let us propose a simple framework for thinking about earnings reinvestment. From a company’s point of view, investment opportunities come in three buckets:

Growing or improving the existing business. In our newspaper example, it was more printing presses. These investments usually carry a high incremental return, but are hard to come by, as they are constrained by demand – the number of printing presses you need is limited by the number of homes you can deliver newspapers to.

Expanding into adjacent businesses, where the assets from your existing business give you some sort of edge over competitors. The NYT has recently gotten into the casual gaming business with some success, rolling it into their existing app. Historically, newspaper companies also reinvested part of their earnings into other media assets, such as magazines, television stations, and cable, which might be considered adjacent if you squint hard enough, but probably didn’t rise to the level of driving any real synergies.

Expanding into unrelated businesses. This is a bad idea unless you are literally Warren Buffett. We already referenced how there was a conglomerate fad in the 1960s that went very badly. Investors have learned through bitter experience that companies that lose focus do badly — it is not for nothing that Peter Lynch dubbed this process “diworsification”.6

Within this framework, it’s easier to see why big companies return most of their cash to shareholders. The most profitable companies today will tend to be more mature, and thus will have fewer opportunities to grow or expand their existing business, especially relative to the gushers of cash they generate. (How profitable are the biggest companies? Apple generated nearly $100 billion of profit in fiscal 2023 after spending $30 billion on R&D, while all US early-stage VC investment last year added up to only $40 billion.) Investors wish to allocate cash to the companies with the best investment opportunities, and so we observe investors moving cash away from large mature companies toward smaller growth companies.

Given that the theory behind this claim is incoherent, it should be no surprise that the evidence shows no relationship between buybacks and investment. Corporate capital expenditure and R&D spending are no lower today than they were before buybacks were popular. Also, the largest buyers of their own stock are Apple, Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft (which combined accounted for a quarter of all S&P 500 buybacks over the last 5 years), which are the same companies that also spend mind-boggling sums investing in AI, self-driving cars, and VR.7

Claim: Nuh-uh, look at this case where a company failed to make an important investment at the same time it was buying back stock!

Here is a common narrative:

An opinion writer decides to scrutinize a company that has stumbled recently.

They discover that the company would be doing much better if it had not passed on some particular investment.

They also learn that this company was buying back stock at the same time it was passing on this investment.

They triumphantly conclude that the stock buyback caused the company to miss the investment, and was therefore the root cause of the company’s misfortune. They then pen a thinkpiece about how buybacks are ruining Corporate America, with this particular example as Exhibit A.

For a concrete example, we previously looked at an NYT op-ed that made this argument at the time Southwest had an operating meltdown over Christmas: Southwest was buying back stock at the same time it failed to upgrade its scheduling software, therefore stock buybacks were a root cause of Southwest’s woes.

This line of reasoning is completely fallacious, and you see it everywhere.

First of all, the writer implies that they have uncovered a correlation between major companies that repurchase stock and major companies that pass on good investments, when they have done nothing of the sort. This is because substantially all profitable major companies buy back stock as a matter of policy. 429 members of the S&P 500 (that is, 86%) bought back stock in 2023 alone. Extend the window more than 12 months, and you will likely find that basically every profitable company has engaged in some sort of stock buyback in the recent past. Of course every investigation of a struggling company will turn up a stock buyback in the past; every investigation of a successful company will uncover a past repurchase as well. All major profitable companies buy back stock!

In addition, we know that 100% of all companies regret passing on some past investment. (Who among us doesn’t?) If you ran the investigation the opposite direction, examining companies that bought back stock, you would find that they all have many investment decisions they wish they could have back. This would also show nothing. The Venn diagram of Major Companies That Repurchased Stock and Major Companies That Missed an Important Investment isn’t even a circle, it’s just the rectangular set labeled “Major Companies”.

The problem with the entire premise the false analogy between a household budget and a corporate budget (again). People assume that any missed investment is due to some cash constraint, when that is never going to be the case at a big company that always generates more cash than they know what to do with.

Bad investment decisions are just bad investment decisions: they usually result from some other less obvious organizational constraint (such as a cultural resistance to change, or limited bandwidth to implement change) or just plain old bad judgment. People tend to assume that most difficult problems can be solved by writing a check, but if that were the case, big companies would be unbeatable, when in reality they come and go.

Of course it is still possible that there is still some causal relationship here; maybe companies that spend more on buybacks make worse investment decisions. If this were the case, however, we would expect to see some anecdotes where a company passed up on an investment specifically so it could make a larger buyback. We actually have anecdotes like this when it comes to dividends; here is a story about GE during the depths of the financial crisis from Power Failure, which we reviewed in the last edition:

On January 24 [2009], [GE CEO Jeff Immelt] announced that GE would keep its dividend at $1.24 for 2009 and would perhaps cut it in 2010, but only if necessary.

…

After forty-five minutes of debate at the board meeting, Ralph Larsen, the lead director and former CEO of Johnson & Johnson, announced the dividend would have to be cut. “That’s just the way it is,” Larsen told Jeff.

…

After Larsen ruled on the dividend, Jeff said he felt like “a cub getting my ears boxed by an elder lion…No matter how dire the extenuating circumstances…I didn’t want to be the CEO who cut GE’s storied dividend for the first time since the Great Depression,” he recalled.

Even though Immelt was eventually overruled, one can see why he wanted to keep paying a large dividend, even when his company desperately needed to preserve cash. He viewed the dividend as a public commitment, and one does not backtrack on public commitments lightly. And by the same token one can see why the board merely wanted to cut the dividend, instead of eliminating it entirely, which would be the common sense action for a company in financial distress. Later that year, GE ended up having to sell NBCU to Comcast at a deep discount in order to shore up the balance sheet, a move they would later deeply regret.

This story is actually a strong argument in favor of buybacks. Many companies pride themselves on an unbroken dividend streak stretching back decades, but no one strives for an extended repurchase streak. A company can just shut off buybacks for a couple of years with no repercussions, as the NYT did in 2020 and 2021.

When this newsletter last touched on the subject of buybacks, we said:

[W]e should consider banning buybacks because there is no other topic on earth that causes so many otherwise smart people to contort themselves into logical pretzels and embarrass themselves in public…everything was fine back when everyone was mostly just paying out dividends, so maybe we should think about just going back to that and saving everyone the brain damage.

Buybacks probably don’t matter. There exists another very close substitute, dividends, which produces almost the exact same end result with none of the toxic discourse.

Buybacks are only worth examining because they are a perfect example of how dumb economic ideas take hold in the minds of intelligent people and refuse to let go. Even though the buyback debate has almost zero real stakes, the same cannot be said of housing, trade, price controls, or any of the numerous other issues where popular economic myths lead to destructive public policy.

Stock buybacks would seem to be a strangely arcane topic for the average person to get worked up about. Who cares about the specific financial pipes that your savings flow through to end up backing a promising project?

We get angry about stock buybacks because our brains work from a series of false analogies to assemble a narrative that triggers strong emotions: we imagine that stock buybacks pit big corporations against everyday workers, demonstrate executive greed, and accelerate the decline of great organizations. The other major financial topic that gets such a reaction is high-speed trading, another case where normal people get very angry about a topic they do not remotely understand because they mistakenly believe it represents some great injustice.

Adam Mastroianni has a great recent post that relates to this topic. He observes that a lot of complicated math was figured out by the ancients, thousands of years ago, but a lot of simpler facts about nature were a mystery until very recently: for example no one knew that objects of different masses fall at the same speed until someone thought to do an experiment in the 1600s, and no one thought to figure out the rules of heredity until Mendel did some experiments in the 1800s.

He connects this to what psychologists call the illusion of explanatory depth: the idea that people believe they have a deep understanding of a given topic, when in fact they are only working from a folk theory, an incomplete and incorrect intuitive model of a subject. When you are familiar with some subject, and you have some mental model of it that works well enough for your purposes, you incorrectly conclude that you have a real understanding of it, and explore no further. The illusion is only shattered when you are forced to write out a coherent explanation of the topic in your own words. (The original experiment asks people to explain everyday objects like toilets and car batteries.) Mastroianni states:

This, I think, explains the curious course of our scientific discovery. You might think that we discover things in order from most intuitive to least intuitive. No, thanks to the illusion of explanatory depth, it often goes the opposite way: we discover the least obvious things first, because those are things that we realize we don't understand.

He concludes that the key to progress is to break the illusion of explanatory depth; people didn’t explore heredity and physics for many centuries because they were working from folk theories that mostly worked well enough, but once they realized how little they actually knew, they made quick progress by formulating theories and then rigorously verifying them (or discarding them) through careful experiments.

Folk theories are as prevalent in economics as they are in science. People use intuitive models and heuristics that actually manage to work well enough in day-to-day life, but backfire badly when applied to create economic policy because they contain weaknesses that emerge when they are used to model the system as a whole.

For example, we talk here sometimes about common examples of counterproductive housing policy, where for example a government might propose subsidies for new homebuyers while placing strict limits on the production of new homes. According to folk theory, the subsidy will obviously make new homes more affordable, but a more careful model will show that housing will in fact not become more affordable at all: houses will be no more abundant than they were before, and the extra subsidy will simply cause homebuyers to bid up the price of existing homes, fully negating the value of the subsidy to the homebuyer and transferring the subsidy to selling homeowners.

It is easy to see here how folk theory works well in day-to-day life but breaks down when considering the economy as a whole: we navigate the world through the abstraction of money, and individually we can procure more goods and services by obtaining more money and outbidding our neighbor for scarce resources, but the economy as a whole is constrained by the total amount goods and services produced, and there is no neighbor that can be outbid.

The illusion of explanatory depth explains how the Times Guild could be so confident and yet so mistaken about stock buybacks: even the brightest minds are easily fooled into thinking they have a deep understanding of a topic that they only have a superficial familiarity with. Often, the biggest obstacle to learning is having the awareness to realize that most of one’s beliefs derive from unsupported folk theories, and the key to knowledge is to have the discipline to dispose of that folk theory when a more rigorous and evidence-based model comes along to contradict it.8

It would be wonderful if proven new discoveries were immediately widely accepted, but in reality, smart people tend to cling to folk theories long after being presented with conclusive evidence that contradicts them. We are usually unaware that we are operating from folk theories, and over time, these folk theories become ingrained in our minds as core truths, and as we use them and teach them, they become wrapped up with our egos and identities, and we form communities around them. When these folk theories are challenged, we instinctively look for any way to defend them, as a way to protect our own status and internal narratives.

One popular story about this process plays out is, of course, Moneyball.9 But as it specifically pertains to economics, Paul Krugman wrote a classic essay exploring this subject in 1996, back when free trade was a hot topic. In it, he expressed shock that so many intellectuals of the day failed to comprehend and publicly opposed the basic concept of comparative advantage, an idea that was originally formulated and fully explained in the 1800s. His thesis was as follows:

(i) At the shallowest level, some intellectuals reject comparative advantage simply out of a desire to be intellectually fashionable. Free trade, they are aware, has some sort of iconic status among economists; so, in a culture that always prizes the avant-garde, attacking that icon is seen as a way to seem daring and unconventional.

(ii) At a deeper level, comparative advantage is a harder concept than it seems, because like any scientific concept it is actually part of a dense web of linked ideas. A trained economist looks at the simple Ricardian model and sees a story that can be told in a few minutes; but in fact to tell that story so quickly one must presume that one's audience understands a number of other stories involving how competitive markets work, what determines wages, how the balance of payments adds up, and so on.

(iii) At the deepest level, opposition to comparative advantage -- like opposition to the theory of evolution -- reflects the aversion of many intellectuals to an essentially mathematical way of understanding the world.

Three decades later, we can see very little has changed. Debunked economic folk theories are still sold as avant-garde, and their inherent complexities and contradictions are actually highlighted to appeal to insecure midwits. The key to breaking free of folk theories is to have to write out how the theory maps to the evidence, but we exempt folk theories from the normal standards of logic and evidence: for example, unrepresentative anecdotes are recast as “lived experience”, and mishandled or outright fabricated data is presented as unassailable proof.

There is a full set of widely accepted but incoherent talking points that defenders of economic folk theories revert to when challenged: for example, it is often claimed that academic economic models are useless because they cannot describe the world with precision, but it is never explained why folk economic models would be any more reliable by that standard?

Public policy crafted around folk theories is rarely subject to any accountability; when those policies predictably backfire, instead of engaging in introspection, we simply double down on the same failed policies.

Finally, there is a huge incentive for politicians and members of the media to pander to the sensibilities of the public and bestow credibility on debunked folk theories, thus the unsupported claim from the Treasury Department that stock repurchases harm innovation. This creates a cycle where bad ideas manage to retain some legitimacy and never quite go away.

In such an environment, we should always expect to be walking around with some web of debunked ideas in our brains, especially as we get further and further away from our area of expertise. The best solution, to constantly evaluate every theory against the available evidence in a consistent epistemological framework, is perhaps unrealistic. Maybe the next best solution comes from the late Charlie Munger: “Any year that passes in which you don’t destroy one of your best-loved ideas is a wasted year.”

To be clear, when you put your money in a savings account today, it is still ultimately invested in some productive asset – when you put money in a savings account, you are making a short term loan to a bank, and the bank turns around and lends that money to some business. In our story, you are investing directly in a productive asset to make the model more clear, but the economics will still be the same if we layer in abstractions like stock and bank accounts.

Adolph Ochs, the man who built the New York Times, started his newspaper career at the age of 14 as a printer’s devil at the Knoxville Chronicle, before buying the Chattanooga Times with $250 of borrowed money (and $1,500 of assumed debt) at 19, which he managed successfully. Twenty years later, the New York Times was in financial distress, and he had acquired enough of a reputation that the existing investors recruited him to take over the Times.

He managed to secure a majority equity interest in the Times through a combination of equity sweeteners earned by personally subscribing for $75,000 of newly issued bonds, and shares earned as equity compensation that vested after he turned in three consecutive years of profitable operation. His great-great-grandson is chairman of the Times today.

He actually quotes everything in proportion to share price, so a stock might have a dividend yield of 6% and undistributed earnings of 2.5% each year; he finds that while investors focus on the 6%, the 2.5% is a critical factor in determining total return. But you can see the payout ratio here is still 70% (6% divided by (6% + 2.5%)).

Granted, we are hand-waving the Great Depression, M&A booms, etc., but this rounds to being true – mature companies have always returned most of their cash to shareholders.

All that happens when one company buys another for cash is that the owners of the selling company get a one-time dividend, funded by the owners of the acquiring company, who in return get a box that they can extract cash from in the future.

There is a minor version of this where companies will get into the real estate business by developing their own corporate headquarters, and that sometimes goes better: In 1904, the NYT built Times Tower in midtown Manhattan, for which the city named the adjacent square, and which became a lucrative source of ad revenue for future owners. The NYT would later build two other Manhattan headquarters as they grew over the years.

S&P classifies the big tech companies as either Information Technology or Communications Services, and those sectors combined accounted for 43% of all buybacks over the last five years. Financial Services accounted for another 18% of buybacks – that sector includes big banks like Wells Fargo and JP Morgan, which are limited in their ability to retain earnings by regulation, and so have to return most of their profits to investors via buybacks and dividends.

In past editions, we have looked at two other anecdotes describing how this has played out in medicine: the odd story of an experienced Norwegian explorer and scientist who became a vitamin C denialist, after it was conclusively shown that scurvy was caused by a vitamin C deficiency, and the more famous story of how 18th century doctors refused to accept that childbed fever could be prevented by hand-washing, even after they were shown the data.

Thanks for the very detailed overview.

One area of this discussion that I haven't really grasped is stock buybacks in the context of bailouts. I saw a lot of criticism in 2020 and 2021 that airlines invested more in stock buybacks in the 2010s than the cost of federal bailouts in 2020, and arguments that they wouldn't have needed a bailout if they didn't put so much towards buybacks.

I don't know if the stock buybacks are even relevant to this controversy, though. Like you've pointed out numerous times in your writing, the story would be the same if they issued dividends or reinvested a similar amount. The only option that would prevent them from "needing" a bailout (if this was even a necessity) is holding massive cash reserves for a rainy day.

I'm really interested to read your opinions on this, but as I mentioned, my suspicion is this controversy has nothing to do with stock buybacks and everything to do with bailouts.

Perhaps bailouts are a good thing, perhaps they shouldn't happen, perhaps companies should hold large cash reserves, or perhaps the private sector should need to rely on insurance to address rare turbulence. Lots of options -- including ones that I'm not even aware of -- but not much clarity in my mind.

Nice piece. Two observations. First, buybacks are tax advantaged vs dividends, would have been interesting to see your take/incorporating that into the overall analysis. Second, Japanese companies have been notorious for retaining capital and it may explain their terrible returns on capital…(continuing to try and grow despite saturation in that specific end market and not freeing up capital in aggregate to go to its most productive end cases).