Ride-Hailing, Revisited

Is ride-hailing broken?

Over at Full Stack Economics, Timothy B. Lee asks whether Lyft’s business model is broken. As an experiment, Lee drove a Lyft for a week and found that Lyft took a 48% cut of his earnings. It surprises him that Lyft can take nearly half of his earnings and still be losing a billion dollars a year. He concludes that the ride-hailing model might be broken and that Lyft desperately needs to slash its payroll.

We took a look at the ride-hailing model last year and came to a different conclusion – that even though Uber and Lyft are losing money now, ride-hailing is more efficient than the traditional taxi model and will probably displace it permanently. This is a good opportunity to dust off that analysis and see if it can be reconciled with Lee’s findings, and if there are any broader lessons we can learn.

Claim: Lyft took a 48% cut of Lee’s earnings from driving around for a week, therefore Lyft’s overall take rate is probably very high, much higher than the 20% take rate that prevailed in the early days.

To be fair, Lee doesn’t explicitly state this, but it is the premise of the article, so I think it’s a fair reading. Here is what he says:

After that Saturday night trip, I started asking my passengers how much they’d paid and comparing it to what I’d earned. The results were all over the map. I had two trips where I got more than 80 percent of the total fare, including tips. I had a couple of others where I earned less than 30 percent.

I wrapped up my Lyft driving experiment after a week, having completed 100 rides in 46 hours and earning $1,111. Lyft eventually sent me a report showing that passengers had paid a total of $2,139.73 for these rides, so on average I got just 52 percent of what my passengers paid.

Ever since then, I’ve been trying to figure out how Lyft could take such a big cut of passenger revenue and still fail to turn a profit—Lyft says that it lost almost a billion dollars in the first nine months of 2022. The more I’ve looked into it, the more I became convinced that it’s going to take major cost-cutting for Lyft to avoid eventual bankruptcy.

Lee is not alone: his experience aligns with stories from other recent articles, where drivers report only receiving only half of the gross revenue paid by riders.

On the other hand, sources that utilize comprehensive data still pin the average take rate of ride hailing networks like Uber and Lyft at closer to 20%, just like it was a decade ago. While Lyft does not report on take rate, Uber reported a take rate of only 20.2%1 in the most recent quarter. Uber’s ride share business is around three times bigger than Lyft’s, so it should be sufficiently representative of the experience of ride-hailing drivers as a whole. Also, a comprehensive study of all rides on all ride-sharing platforms in New York City (the biggest ride-hailing market) in 2017 finds an average take rate of 16.7%. The authors of that study were pushing for a minimum wage for drivers, so if there was to be any bias, you would expect it to go the other way.

Is it possible that some drivers could experience a take rate of 50%, while the overall average is closer to 20%? Or is the comprehensive data fraudulent?

If the comprehensive data is accurate, we should look to see if there are drivers on the other side of the distribution experiencing a very low take rate.

The Rideshare Guy is a major blog covering the industry from the driver’s perspective, and they had a recent segment on their podcast going over this very topic. One of the hosts shares their personal experience, which includes a lot of rides where Uber actually lost money, and finds that Uber had an overall take rate of only 9% over the 788 rides they gave. (Remember that Lee only gave 100 rides.)

If you think about it, it makes sense that there is a huge variance in driver take rates. Most businesses show significant variance in their take rate and their margins across different segments. Airlines charge much more to fly at peak days and times, or at peak season, or on specific routes where they have little competition; meanwhile, their per-hour operating costs (fuel and labor) should be mostly consistent from flight to flight. Their take rate must be very high on some flights and very low on others.

The ride-hailing networks should be setting their driver payouts and ride prices separately, based on competitive conditions and the responsiveness of supply and demand to price shifts. Like in our airline example, they should have higher margins when there is higher demand. It’s rational for them to continue to offer rides as long as they are making some money, and it’s probably even rational for them to lose money on some rides where it sets them up to make money later (e.g. by repositioning drivers to areas of higher demand, or keeping wait times low).

One of the issues here is publication bias. If there is a lot of variance in experience, the people with the most extreme experiences will be the most likely to shout about it, while people with normal experiences will just shrug and ignore it (unless they happen to run an industry podcast).

Everyone’s personal experience is a small, possibly biased sample, but Lee also accidentally introduced a very particular known bias. A couple of years ago, there was a flurry of hotly contested studies using comprehensive data to look at effective driver wages. One of the studies, done by a team at Cornell, looked at all of the rides given over on Uber and Lyft in Seattle over the course of a week. One of their findings was the existence of a significant cohort of what they termed “casual drivers” (25% of drivers, but only 3% of rides) that drove only a few hours during that week, some of whom had very low effective wages, probably because they were not as strategic about maximizing income. (They were less likely to use both Uber and Lyft simultaneously, for example.)

Lee reports only grossing $24 per hour, while the Cornell study found that the median rideshare driver in their full sample achieved gross earnings of $37 per hour. Granted, these are different cities (Lee is in Washington, DC) and different time periods (the Seattle study is from October 2019), but the divergence is still suggestive. One of the points from the Rideshare Guy segment is that driver income and take rate is highly dependent on driving strategically and taking advantage of bonuses and quests. It’s believable that a journalist driving to collect stories for an article would behave differently than a typical driver focused on making money, and would end up with atypically low earnings and high network take rates as a result.

It’s unlikely that Uber or New York City are somehow publishing fraudulent or incorrect revenue and driver earnings data. What would be the point? Uber is a public company – why would they underreport revenue? The simplest explanation is the most likely explanation: there is a wide variance in driver experience, and the most extreme experiences are the ones that get written up.

This is a good illustration of the idea that “the plural of anecdote is not data”. Also, while Lee is very reasonable in his article, people are sometimes very insistent in extrapolating their personal experience to a broader conclusion about the world. The Rideshare Guy podcasters remark that they got a lot of hate mail just for sharing their data showing a low Uber take rate. People often take any evidence that contradicts their “lived experience” as a personal attack, rather than just as an expected consequence of the variance that exists in the world. If variance exists, then a lot of people will have a “lived experience” that is wildly out of the norm, and what are the odds that you are the only person in the world that exclusively has normal experiences?

This is something we have also seen when looking at housing issues: people that live in booming coastal metros won’t recognize that they are extreme outliers compared to the rest of the country, and they think housing prices are out of control everywhere, rather than in a small minority of cities.

Properly framing personal experience is an everyday problem in business. Whether you are a journalist, an investment analyst, or a product manager, it is essential to get out into the field and try to experience what is going on first-hand. Doing so sheds light on key details that are invisible in the data. One just has to keep in mind that personal experience is only a sample size of one.

Claim: Lyft has higher overhead than a traditional taxi service.

Here is Lee:

Back in 2016, a transportation economist named Hubert Horan crunched the numbers and found that in the pre-Lyft world, about 15 percent of passenger fares (including tips) went to dispatching and other “back office” functions. The other 85 percent went to driver compensation, fuel, and the costs of vehicle ownership and maintenance.

So if Lyft were as operationally lean as a traditional taxi company, the driver would get 85 percent of passenger fares (Lyft drivers pay to maintain and fuel their own vehicles, after all), while Lyft would be able to cover its costs with the other 15 percent. But if my rides are any indication, Lyft is taking way more than 15 percent and still losing a ton of money. It seems that the smartphone revolution didn’t make dispatching cheaper and more efficient, as you might expect. It made it way more expensive.

Since Lyft doesn’t report gross bookings, let’s look at Uber’s latest quarterly numbers (across all segments, including Eats and Freight), presented on an annualized basis:

One misunderstanding here is that the 20% take rate doesn’t encompass all of the direct costs of providing a ride. Credit card fees (which should be about 2% of gross bookings) and insurance (probably a few percentage points more) get absorbed by Uber after the 20% take. All of the billions of dollars of personnel and advertising and legal expenses only come to about 12% of gross bookings: significant, but still less than the 15% of a traditional taxi service.

Now, it is possible that Uber’s expenses are still too high, but for now, that is being absorbed by Uber shareholders, not riders and drivers. Either way, this is a good illustration of the importance of digging into the numbers and the fine print.

Claim: Ride-hailing dispatch is only a small improvement on traditional taxis.

Here is Lee again:

I think it’s overstating things to say that Uber and Lyft haven’t improved on traditional taxis. At a minimum, Uber and Lyft have dramatically improved the reliability of pickups. I’m old enough to remember calling a taxi in the pre-Lyft days and not knowing if it would show up. I think many passengers are willing to pay at least a small premium for that.

…

But with that said, I think Horan is right that these are fairly incremental improvements to the basic taxi business model. Which leaves Uber and Lyft with the same challenging economic model as a traditional taxi company.

There is a common pattern where one wants to compare two products that are mostly similar, but differ greatly across a few dimensions. The most common approach is just to eyeball the problem, and use gut feel to guess how important those dimensions are.

Another approach is to figure out how much consumers value each dimension using data. The goal is to find a test that helps isolate each dimension.

We did this before with dispatch. We know that dispatch does not matter very for a certain subset of traditional taxi rides: rides from the airport, where there is consistent demand, and rides downtown, which can be hailed on the street. On the other hand, dispatch is very important for rides in less dense areas.

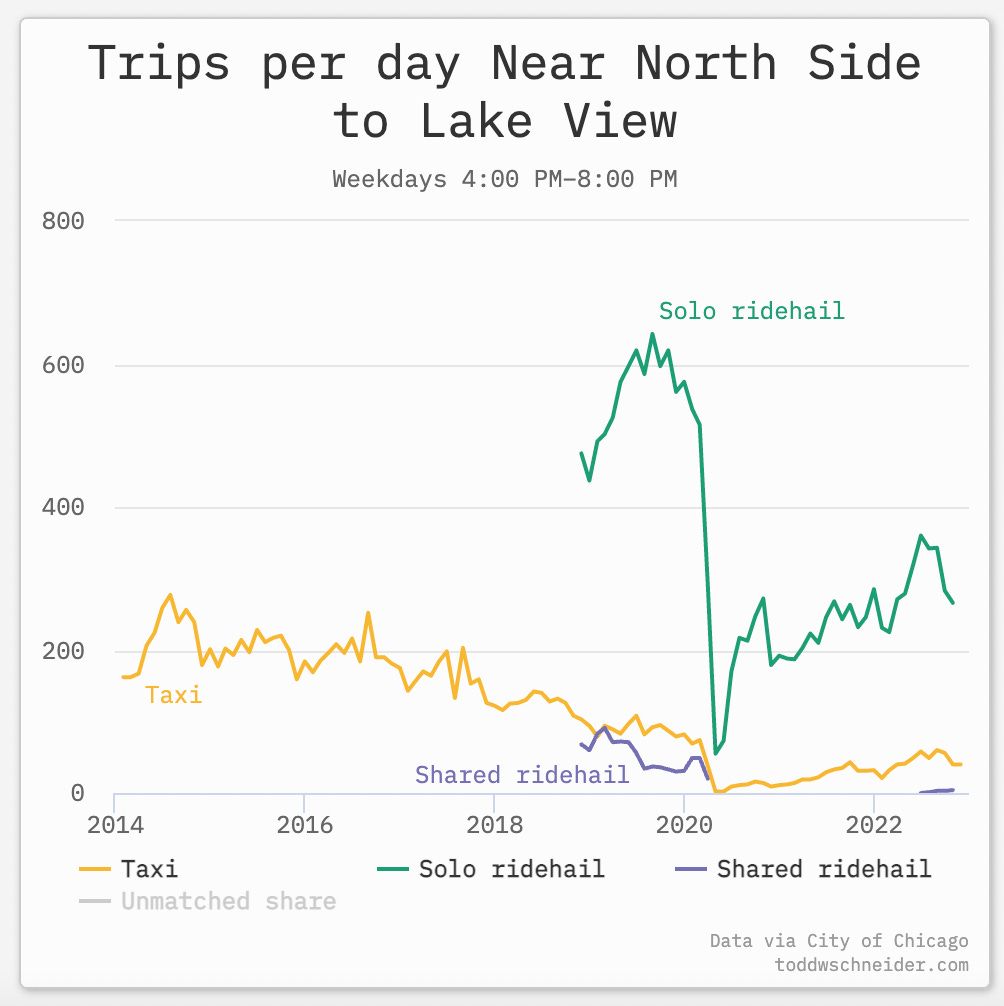

If dispatch is important, then less dense areas should display different demand patterns from than denser areas when ride-hailing entered the market. Via Todd W. Schneider, here are is the evolution of rides in Chicago originating in less dense areas, 5+ miles from downtown, as ride-hailing entered the market (note that while taxi data dates back to 2014, ride-hailing data in Chicago was not available until 2018):

There were barely 8,000 taxi pickups per day in this area before ride-hailing, and now there are over 60,000 per day. This is what we would expect if dispatching was cripplingly bad prior to ride-hailing. (Note that per-mile and per-minute pricing are now about the same between ride-hailing and traditional taxis; the main difference now should be the reliability of dispatching and rider experience.) Compare this to the pattern at Chicago airports, where dispatch is unnecessary:

As expected, taxis held up much better here.

We can also estimate the value of ride-hailing by looking at the premium riders are willing to pay to use ride-hailing instead of taxis. We looked at a major subset of routes where ride-hailing has mostly displaced taxis, despite now being 60% more expensive:

There is a temptation to flatten a problem by making a major simplifying assumption, and then when coming to a conclusion, forget that the conclusion was part of the original simplifying assumption. This is a form of “begging the question”: in this case, start by assuming taxis are probably just about as efficient and valuable as ride-hailing, and after many steps, you will conclude that taxis and ride-hailing are about the same.

This is something we came across with housing as well. One common approach to analyze supply is to look at the overall number of housing units in America compared to the number households. The problem is that household formation is dependent on housing construction: young people will only move out to their own place if there are homes available. Nevertheless, people write housing “analysis” that consists solely of this circular logic; as long as housing formation tracks housing available (as it must by definition), everything must be fine. The correct way to look at the supply/demand balance in a market economy is to focus on the change in price: we use price to ration scarce goods, so high prices are the only reliable indicator as to whether supply is too tight.2

Before we move on, there is an additional interesting detail to note here. Before, we looked at the ratio of dispatch costs and overhead to overall revenue as a measure of efficiency. Here, we can see that this is an invalid approach, since many (if not most) traditional taxi rides don’t involve dispatch at all, while all ride-hailing is electronically dispatched and tracked. Taxis apparently had higher dispatch costs even though they didn’t really serve riders in lower density areas that required dispatch.

This is a common hazard with ratio analysis; for ratios to be comparable, the businesses have to be closely comparable. Once we see that taxis and ride-hailing provide two different bundles that are valued very differently by consumers, then we can no longer directly compare line items. It would actually be fine if ride-hailing was more expensive to operate than traditional taxis once you know that consumers are willing to pay a big premium for it; all that matters is that consumers come out ahead in the end.3 It just happens that ride-hailing is more efficient and a better overall product, as is often the case with new technologies.

In general, one should be very wary of programs that seek to analyze or improve a single variable or a single dimension, to the exclusion of everything else. The goal is to improve overall welfare, not to target a vanity metric. Goodhart’s Law suggests that people will take the easiest path to improving a metric, and the easiest path is often one that worsens overall welfare. Again, we saw this with housing: people propose banning new public amenities in poorer areas to prevent gentrification and keep rents down, something that might keep rents down but will not make residents of those neighborhoods better off overall, much less society at large.

Claim: Lyft might be screwed.

Ok, this one has a better chance of possibly being true. Here is where I remind everyone that this is not investment advice, I don’t have any investment position in any ride-hailing company or financial relationship to the industry whatsoever. This is just a fun intellectual exercise.

Here are Lyft and Uber side-by-side in the most recent quarter (ignoring gross bookings, which Lyft doesn’t report):

Part of the original investment thesis for Uber and Lyft in the early days is that ride-hailing might be a winner-take-all business, with monopoly margins for the winner. One idea was that local scale would be essential to keep down wait times, something that doesn’t seem to be the case. But another part of the equation is the high fixed costs involved: Uber is able to spread their fixed product and engineering costs and overhead costs over a much larger user base.

Keeping in mind that Uber and Lyft are not directly comparable – Uber is global, and also runs a food delivery business – overall, Uber spends triple what Lyft does on R&D and G&A, but that as a percentage of revenue, they only spend at half the level of Lyft.

So far, Lyft’s losses have been manageable. They were able to compensate employees with highly valued stock, which kept a lid on cash outflows. However, in the last year, the stock has fallen 76%, and the market cap of the company is now below $4 billion. (Lyft has raised about $5 billion to date, and they reportedly turned down a $6 billion offer from GM in 2016.) A lower stock price makes stock-based compensation much more dilutive, if they continue to issue the same dollar value of stock to employees.

Lyft has announced layoffs last month, and will no doubt keep cutting to try to get to profitability. But this highlights a common danger for industries with major economies of scale; unless there are countervailing forces that benefit the smaller competitors, or significant points of differentiation, the best case scenario for subscale players is survival. As Warren Buffett once said of the newspaper business, it can turn into “survival of the fattest”.

The headline take rate is 28%, but you have to read the footnotes, which says that 28% excludes a “benefit from business model changes in the UK”, and the adjusted take rate excluding this is 20.2%. The “business model change” seems to be a ruling that forces Uber to book the entire cost of a ride as revenue, rather than just the share they retain after paying drivers. This doesn’t change anything about their net take in reality, but it distorts their reporting – if I understand it correctly, for the UK only, by rule they are reporting a 100% take rate, and the share that goes to drivers gets booked in cost of revenue instead.

You have the same issue just looking at measures of national housing supply. A flat measure of national housing units ignores the difference that a unit in Manhattan might be a hundred times more valuable than a unit in Youngstown.

Glad to see the faulty reasoning of the original post rebutted. Thanks for putting in the work to address so thoughtfully.

Reminds me of the week or so I DoorDashed. Probably made less than minimum wage after expenses, but those insulated bags are great!