Ride-Hailing: Is It Sustainable?

Do ride-hailing companies have any pricing power? A case study

Here is an excerpt of a recent article in Mother Jones provocatively titled “The Man Who Called Bullshit on Uber”:1

[In November 2016], Hubert Horan, a little-known expert on the airline industry, wrote a blog post for an equally little-known website, called Naked Capitalism, that went in a different direction. Horan’s thesis was that Uber was a tremendously unprofitable, inefficient, and not particularly innovative company that would make money only if it bought its way to an unregulated monopoly.

Compared to the Forbes piece and many others like it, Horan’s article was a fiduciary root canal. (“There is no simple relationship between EBITAR contribution and GAAP profitability,” reads part of one sentence.) The goal was to show that Uber was hugely unprofitable and how, in the event that it did succeed, profit would come from hurting consumers and overall economic welfare by cornering the taxi market.

Horan, who started consulting in the airline industry after getting his MBA at Yale in 1980, has now written 26 more installments of his Uber series. When combined as PDFs, the posts run 193 pages. They reveal him to be much more a Cassandra than a crank. Uber has lost in the neighborhood of $28 billion since it launched in 2009. Its rides now cost far more than cabs in many major cities, its workers are as exploited as ever, and taxi drivers face massive debts, partly as a result of its business practices. Consumers, meanwhile, are shocked to learn what the rides investors have been subsidizing actually cost.

The market currently values Uber at $78 billion, so Horan’s thesis that it is actually worthless certainly qualifies as contrarian. And yet, the idea is not so easy to dismiss out of hand.

If I told you that Google was worthless, a scam that will inevitably collapse, you would tell me that everyone uses Google and Google makes a kajillion dollars a year and that should be adequate evidence that it is a real, innovative, sustainable business. Even if I knew nothing about the internet or search, I could conclude from the revealed preference of consumers and Google’s immense profits that there is something there.

Now if I told you Uber was worthless, you would tell me that everyone uses Uber and I might say “true, but what about the billions of dollars of cash Uber burns every year”? And you might say, “well, it’s complicated, for starters, have you heard of adjusted EBITDA?”

A business that loses money is not inherently unsustainable or damaging to consumer welfare. For example, the airline industry has been notorious for losing money throughout its existence; aside from some periods of government subsidy and protection, the US airline industry has never turned a consistent profit in its entire century-long existence.2 In the opening decade of the 2000s, the US airline industry somehow lost a combined $56 billion.3

This does not imply that the airlines will all eventually collapse and we will soon all be traveling cross-country by covered wagon. The profits (or losses) of an industry are more a function of competitive dynamics than of the underlying utility of the product. A commercial airliner still travels at ten times the speed of a car for a fifth of the per-mile price, but the individual airlines themselves will only make money if they can rationalize pricing and capacity.

Airlines that collapse merely transfer their planes to other airlines (both new and existing), and air travel as a whole continues to grow. Airline losses simply represent a transfer of wealth from airline investors to passengers and employees.

On the other hand, an industry that consistently loses money raises questions about the underlying economic model. Horan has been vocal about Uber for years, publishing his bearish thesis in the Transportation Law Journal, American Affairs, and Promarket (a publication affiliated with the University of Chicago Booth School of Business). He has the rare distinction of recently having received positive coverage in The American Conservative as well as this article in the left-wing Mother Jones. Clearly, his message has struck a nerve with a diverse audience.

The temptation when analyzing a stock is to jump straight to the fun stuff - in the case of Uber, the future of self-driving cars, or perhaps the theoretically vast total addressable market. In fact, the first step in analyzing a business should always be to figure out how exactly the business is supposed to sustainably make money, and in so doing one should get some insight into pricing power and long-term profitability. Horan’s model of Uber is useful as a sort of null hypothesis - he believes Uber can never make money. So let’s tear it down and find out: is Horan a crank or a Cassandra?

Uber is a software company stapled to a taxi service. Uber the software company creates taxi service software and then hands it to Uber the taxi service. Uber the taxi service then deploys the software in order to run a more effective transportation company. If the cost of developing the software is lower than the benefit the taxi service gets from using it, Uber should eventually be able to make money.

Horan’s thesis boils down to the idea that the software is not very valuable. In his opinion, a taxi service is a taxi service. No matter how you dress it up, you have to pay the driver, you have to pay for fuel, and you have to pay for the vehicle. Having a moving dot on your iPhone looks nice, but the overall package does not improve efficiency and only marginally improves the passenger experience. Worse yet, Uber is no good at running an efficient taxi service, which is only to be expected from a company that outsources scheduling and maintenance to their drivers. In his opinion, Uber’s persistent cash burn is supposedly evidence of this.

The bull case for ride-hailing is that the software is very valuable; it changes everything about the experience for both riders and drivers, and it improves overall efficiency. In the old days, you had to call a human dispatcher, describe where you were, hope that they knew of a cab that might be close to you, and hope it eventually showed up. Now you press a button on your phone, and the software matches you with a driver, and you have full transparency as to where your ride is.

You are undoubtedly familiar with the most popular features of a modern ride-hailing app: As a rider, you get your pricing upfront, payment is automatic, your driver is being monitored, and you can see where your ride is at all times. As a driver, you can generally start and stop working whenever you want (although you will be paid more if you drive where and when there is high demand), and you also have some transparency into who your rider is. Also, the software is supposed to be good at predicting where demand will be, nudging you toward those areas, and generally ensuring that you will spend more time carrying passengers than looking for a new fare.

The true utility of the software is really supposed to show up in the second order impact: higher liquidity. The direct utility of the software attracts more riders and drivers, which lowers wait times and increases utilization, which is what riders and drivers really want. A car service that forces you to wait up to 30 minutes for a 10 minute ride is not very useful, no matter how cheap it is. Meanwhile, drivers only get paid for the fraction of time they are actually carrying a passenger - if they can keep the car utilized for 80% of the time instead of 40%, they will double their income if fares are the same.

Higher utilization and lower wait times attracts more riders and drivers, which results in higher utilization and lower wait times, which attracts more riders and drivers, and so on in a flywheel. This is all online marketplaces 101, and in fact Uber investor and board member Bill Gurley basically laid this case out for Uber back in 2014, just two years after UberX was launched.

The potential economics of online marketplaces have been widely understood since the days of eBay, a quarter-century ago. Scores of entrepreneurs since have tried to launch online marketplaces, building and polishing software and subsidizing early users to kickstart the flywheel. Some, like Etsy, succeeded and are worth billions, while many others failed to provide enough utility to make the business self-sustaining and folded. For all we know, Uber and Lyft are still subsidizing early users and have no path to make the business viable.

To see which side is correct, we need to observe how much riders and drivers value the software, and compare that to the cost of the software. To summarize, if the software is truly valuable, we should usually observe most of the following:

Ubers and Lyfts will generally have higher utilization rates than taxis; that is, taxis will spend a larger share of time driving around empty, looking for a ride, than Ubers or Lyfts do;

Ubers and Lyfts will have much higher geographic coverage and lower wait times;

All things being equal, riders will pay more for an Uber or Lyft than they would for a taxi;

At the same price, riders will usually opt for an Uber or Lyft over a taxi, and they will take many more rides with Uber and Lyft than they previously took with taxis.

Conversely, if Horan is correct, we will observe that users are mostly indifferent between Ubers and taxis at the same price, and that there was be little change in the total number of total car service rides taken since Uber and Lyft became available (holding price constant), and Ubers and taxis will have similar geographic coverage and utilization rates.

To get our bearings, let’s start with the basic numbers we have about Uber, as of the most recent quarter. “Gross Bookings” is all the money people spend on Uber (rides) and Uber Eats, excluding tips. Last quarter, that was $23.1 billion, meaning that Uber is pulling in over $92 billion a year.

“Loss from operations” represents the GAAP operating loss, which totaled $572 million. (For simplicity, we will stick with conservative GAAP measures here, except for gross bookings.) That translates to a bit over $2 billion a year.

So, Uber is bringing in $92 billion a year, but spending $94 billion a year. For every $1 you spend with Uber, they are spending a bit over $1.02 to provide you with your ride or your meal.4 That is not ideal, but perhaps not insurmountable. It is not Google, but it is also not MoviePass. It is at least plausible that they might have enough pricing power to raise their take rate enough to cover that.

The income statement above shows that they are recording $22 billion per year in operating expenses, which are the outflows outside of the ordinary share of Gross Bookings handed over to the driver or the restaurant. It is important to note that some portion of that $22 billion represents investment that will grow the business in the future, not expenditure required to keep the business running now.

Uber might spend to open up an operation in a new city, or they might spend on upfront incentives to recruit new drivers who they expect will be on the platform for some time. They might even spend on incentives to get new users to make their first purchase, in the hopes that they will order again in the future, preferably without checking Doordash or Lyft for competitive prices. All of that gets clumped together with ordinary expenses like credit card fees, salaries for customer support agents, and stock options for the executive team.

In that sense, it is perhaps not precisely accurate to say that they are losing two cents for every dollar they take in. We do not have a good way to estimate “growth” vs. “maintenance” expenses, and perhaps at this stage the difference is immaterial for Uber, but it is an important concept to keep in mind.

Another line to highlight is “Research and development”, which is all the money that Uber spends directly on product managers, designers, and software developers: $2 billion a year. The great thing about software is that it scales well - once you’ve built it, it costs about the same whether a hundred people or a hundred million people are using it simultaneously. (Emphasis on “about” - clearly, software that works at that scale is bound to be more complicated and expensive, and Uber must have a heck of an AWS bill, but the total cost per user generally goes way down as you get millions of users.)

Not all expenses related to software are in the research and development line - hosting bills end up in cost of revenue, the salaries of the HR people that support the developers might be in G&A, and so on. Even if we are generous and say that the total software bill is $4 billion a year, that means that software only represents 4% of the cost of your ride or delivery order. Is their software good enough to make your user experience 4% better or cheaper than that of a traditional taxi? It seems at least plausible, but we have to check the data to be sure.

A final note: For now, the Eats business has surpassed the traditional Rides business in volume - Eats currently accounts for $50 billion in annual gross bookings, vs. $40 billion for Rides. If you believe Uber’s non-GAAP accounting, Eats accounts for all of the losses and Rides is breakeven or profitable, depending on how you allocate shared costs, and losses in Eats are understandable since they are spending on acquiring new users and restaurants and drivers and doing so quite rapidly.

If we believe the ride-hailing business is already profitable, this whole exercise becomes redundant, so we will ignore all of the non-GAAP accounting for now. The economic logic of the meals and rides businesses should be similar anyway, so strictly for this exercise we will ignore the distinction - but keep in mind that to properly analyze the business, one would want to separate the two.

The wonderful thing about analyzing a transportation business is that it is highly regulated, which frequently means useful public data sets a mere Google search away. Chicago and New York both release some of their ride-hailing and taxi data, which data scientist Todd W. Schneider has used to create some wonderful public dashboards, accessible here. He also links to the original datasets, which you would want to use to do any serious diligence, but what he has created is more than enough for this exercise.

Ride-hailing is mostly concentrated in large, dense cities; in 2017, 70% of all ride-hailing trips in the US were in the nine largest cities. Looking at two of the largest of these cities should give us a useful picture of the industry. According to his data, the taxi and ride-hailing market was about $2 billion a year within the Chicago city limits before Covid, and about $6 billion a year in New York.

We will mostly focus on Chicago, since Chicago has fare data for ride-hailing, but Schenider’s dashboard shows that New York mostly exhibits the same trends, even though it is an unusual market.

Let’s start with an overview of the ride-hailing market in Chicago. Note that the taxi dataset in Chicago goes back to the beginning of 2014, while the ride-hailing dataset doesn’t start until the end of 2018, but this won’t be a problem for our purposes. UberX did not start until the middle of 2012, and we can see from the New York dataset that ride-hailing was fairly small even at the beginning of 2015, so we will get a full sense of how ride-hailing affected the taxi market by starting in 2014.

There is a popular conception that ride-hailing grew by undercutting and taking market share from taxis, but the data shows that not really to be the case. Immediately prior to Covid, ride-hailing was a $5 million a day market in Chicago, while taxis went from $1.1 million a day in February 2015 to $600,000 per day in February 2020. Roughly speaking, 90% of the ride-hailing market is new, while 10% came from taxis. This lends a lot of credence to the theory that the ride-hailing software created a valuable new market, and undermines Horan’s theory that ride-hailing is a predatory pricing scheme targeted at taxis.

We also see that ride-hailing is on average about a third cheaper than taxis on a per-mile basis. (This understates the price difference, since tipping is much higher for taxis.) That said, lower prices alone are unlikely to account for the magnitude of ride-hailing demand in Chicago. The demand for transportation can be elastic, but almost nothing is elastic enough to trigger a 400% increase in demand from a 30% price cut.

Also, we observe that taxis have managed to maintain a significant portion of their original volume in spite of much higher average prices, which implies that there is some hidden heterogeneity in the market we should try to uncover.

Keep in mind that the fare difference does not tell us anything directly about driver compensation per hour, since compensation is a function of fare per mile, speed and utilization (as well as the take rate of the dispatch company). A driver can make up a lower fare per mile by driving faster (increasing compensation per hour) or through higher utilization (as we discussed earlier). We will look at utilization later, but above we see that speed appears to be a meaningful factor - the fare per minute gap was only 17% before Covid, perhaps because ride-hailing is more likely to be used when and where there is less traffic. Also note that the fare per hour has been significantly higher for ride-hail than taxis since the pandemic, due to the flexible pricing of the ride-hail model. We can exploit this natural experiment later to estimate how much users prefer ride-hail over taxis, all things being equal.

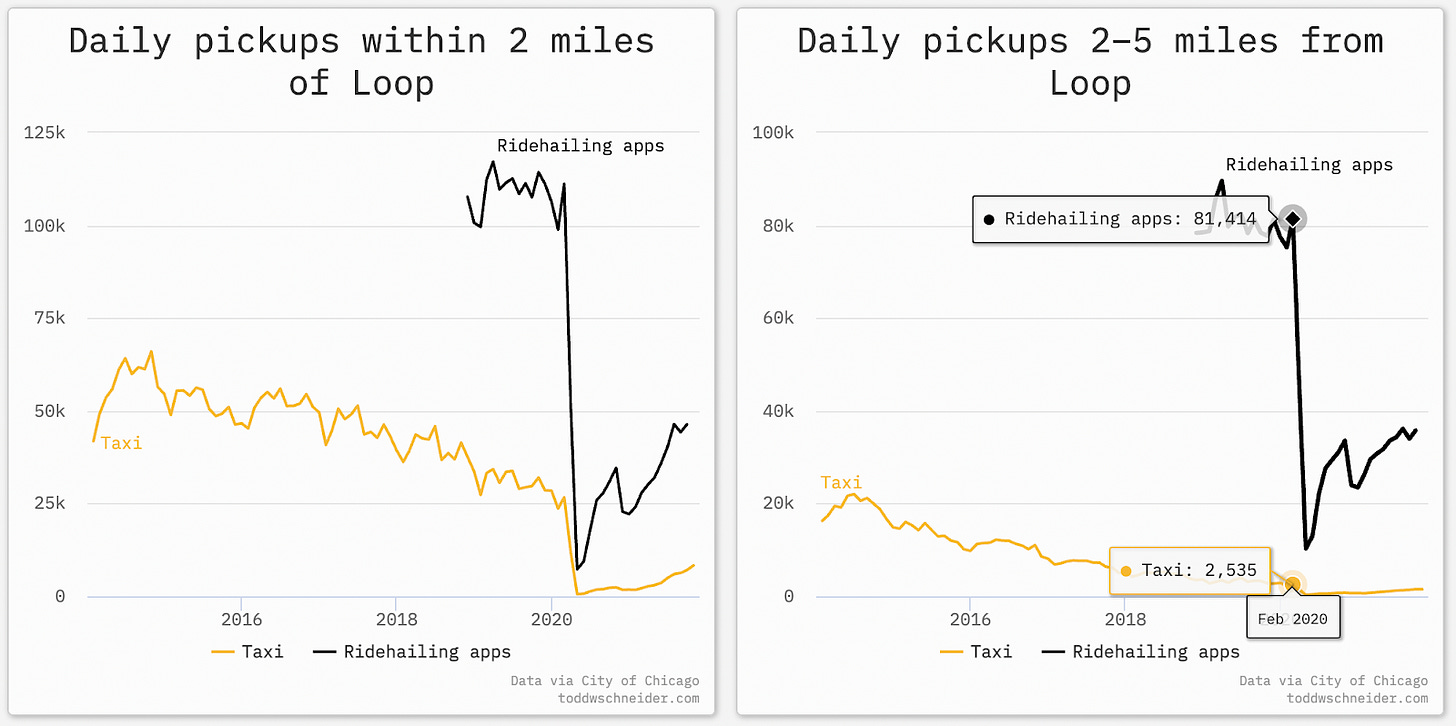

Here we can see that taxi pickups have always been very geographically concentrated. Chicago is a huge city (234 square miles), but taxi pickups have always mostly been within a very small slice of the city, either within two miles of the Loop (downtown) or at the airport - probably 10 square miles combined at the most. By contrast, ride-hailing is much more evenly spread across the city; over half of rides start more than 2 miles from downtown, in semi-dense residential areas.

These charts make it clear that taxi service was close to non-existent in neighborhoods outside of downtown prior to ride-hailing. Ride-hailing took a little bit of the market from taxis downtown, but it looks a lot less like ride-hailing undercut taxis and a lot more like ride-hailing created a new market.

Way back in 2014, right after UberX got started, UC Berkeley did a survey to understand ride-hailing in San Francisco (emphasis mine):

When calling a taxi to their home, only 35% of San Francisco residents said they usually waited less than ten minutes on a weekday during the day; on nights and weekends, this figure dropped to 16%. By comparison, close to 90% of ridesourcing respondents said they waited ten minutes or less, at all times, and 67% waited five minutes or less. Ridesourcing wait times are also much more consistent than those of taxis: whereas taxi waits are more variable by time and day, ridesourcing customers could expect a wait of ten minutes or less regardless of day or time.

And here is what the Chicago Tribune reported in 2019 (emphasis mine):

In March 2019, for example, ride-share drivers made more than 47,000 pickups in the low-income, majority African-American neighborhood of Englewood, compared with 85 cab pickups in March 2017, the most recent comparable information available.

In most Chicago neighborhoods, ride-hailing has 95%+ market share, and is at least an order of magnitude bigger than taxis ever were. For most of the city, taxis were too unreliable to be useful even before Uber and Lyft entered the scene, so ride-hailing was the basically only game in town by default. This seems to definitively contradict Horan’s thesis, which is that ride-hailing is about predatory pricing and undercutting taxis, and that improving liquidity to this extent should be impossible.

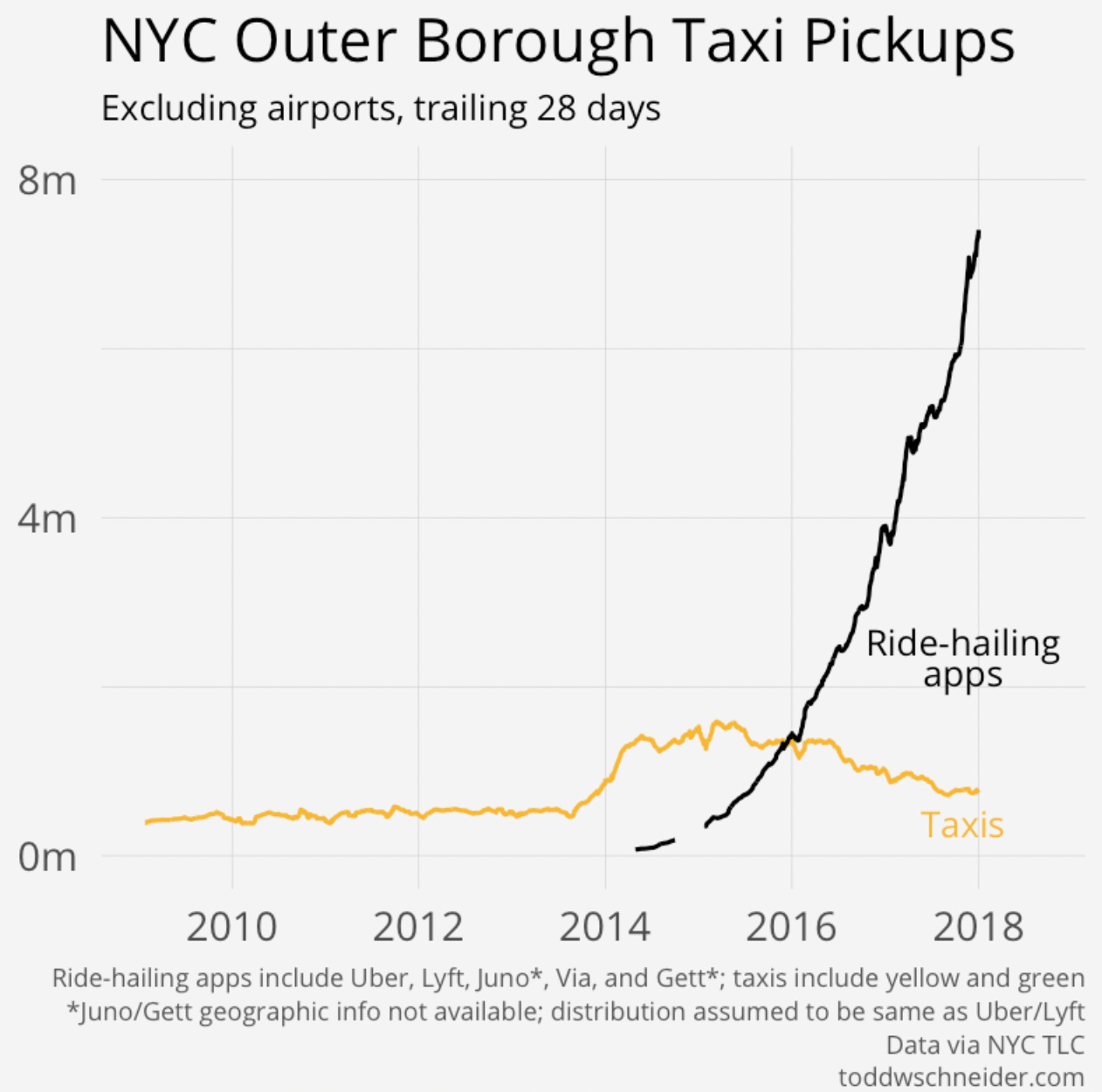

This is not a uniquely Chicago phenomenon; here is the same graph Schneider produced for the outer boroughs of New York, up to 2018. A major part of the ride-hailing story is coverage of markets where it has always effectively been the only option, short of taking public transportation, which is often much slower, and sometimes completely impractical.

Airports provide an interesting potential natural experiment. Airports should take liquidity out of the picture to some extent, as airports have always supplied large and consistent demand for car service. Both taxis and ride-hailing should be equally able to offer short wait times, so the only difference is price and the overall user experience.

Airports are where taxis have held up the best - remarkably, taxis kept the number of pickups consistent even as ride-hailing surged past it, implying the total airport market has grown considerably. This might be because ride-hailing has made it more realistic for travelers to get around a city without a rental car for the duration of their trip; it has been well-documented that Uber and Lyft have cut into demand for rental cars at airports. At the same time, Uber and Lyft have also created a new source of car rental demand, for drivers renting on a weekly basis. Ride-hailing, taxis, and car rental are all substitutes, but they are all complements to some extent as well.

Ultimately, this means that there are too many moving parts to arrive at any useful conclusions from looking at airport demand at a high level. Taxis have retained some market share, but anecdotally this seems to be because people opt for fixed rate taxis when there is surge pricing and/or there are no ride-hailing cars available.

Schneider also includes an intriguing case study of a single popular route during rush hour, a 15-20 minute trip from downtown to Lake View, which is a wealthy region a couple of miles to the north that includes neighborhoods like Wrigleyville. This route is very well served by inexpensive public transportation, so it may not be representative, but it does begin downtown (in this dataset, the Near North Side includes the part of downtown north of the Chicago River), where taxis should generally be more available and convenient.

Ride-hail was about the same price as a taxi ride before Covid, probably due to rush hour surge pricing, but ride hail peaked at 600 rides per day, triple the 200 rides per day taxis served before ride-hail came along. Post-Covid, ride-hail is almost double the price of a taxi, and still manages 200 rides a day, which is what taxis managed before ride-hail. Again, this particular route is bound to have a very wealthy ridership, and perhaps the pandemic is shifting some users away from public transportation, but it gives some possible sense of the price gap that it takes to make some users indifferent between taxis and ride-hail, even when wait times are not as large of a factor.

It is also interesting to look at the ride-hail market for the Chicago as a whole; returning to the charts from the beginning, the average cost per mile of ride-hail is for now equal to the current and historical average cost per mile of taxis, but ride-hail is currently running at $3.5 million per day, compared to $1.5 million per day for taxis at the same time in 2014, before ride-hail really entered the picture. Prices are the same (on average), but consumption of for-hire vehicle service has more than doubled, all thanks to ride-hail.

The immediate post-pandemic (or late-pandemic) environment has created a very interesting natural experiment, showing what would happen to ride-hail with much higher prices; as it turns out, people love it and stick with it.

There has been a recent proliferation of bad takes on how Uber and Lyft are now forcing us to pay the “true” cost of ride-hailing. In reality, the data seems to be clear that riders came back faster than drivers, who are reluctant to pick up strangers during an ongoing pandemic (especially if they can make nearly as much delivering food). Ride-hail companies are trying to balance supply and demand by raising prices, effectively creating hazard pay for drivers while keeping rides available for those who are willing to pay. Taxis are stuck to fixed rates, and as a result they have not returned in great numbers, even though they are making a bit more because of higher utilization and/or speed.

We might expect higher prices to be a temporary phenomenon, but either way, it is important to remember that higher prices that get passed on to drivers at best only marginally improve the economics of ride-hailing apps, as long take rates stay constant, as is the case now. Higher prices result in fewer trips, so higher prices may not translate into significantly more revenue. Ride-hailing companies may see a bit of margin improvement from higher prices if they have some operating costs that are actually tied to the number of rides or miles driven, but it is not clear they have any such costs that are significant.

To grow profitability significantly, the ride-hailing companies will have to increase their take rate, reduce spending on incentives to passengers and drivers (which is effectively just another way of raising their take rate), and/or find other cost efficiencies that they decline to pass on to riders and drivers.

It seems clear from the data that competition from taxis does not force ride-hailing companies to lose money any more than competition from trains force airlines to lose money. If Uber is truly losing money on ride-hailing, it is because they have chosen to keep take rates low, either to keep pressure on Lyft or to grow usage. From the perspective of the rider, ride-hailing is massively superior to taxis on almost every dimension and in almost every use case; sometimes, software really works!

So far we have seen that users strongly prefer ride-hailing over taxis. Lower prices alone cannot explain it, since expensive ride-hailing now is far more popular than cheaper taxis ever were, at a level that cannot be explained by a pandemic-related temporary aversion to public transportation.

Lower wait times and higher reliability seem to be the biggest factors, particularly in less dense areas that never had much taxi service, but people also seem to significantly prefer the ride-hailing user experience, as we can see in downtown and airport pickups, where wait times have not changed much but people have demonstrated a willingness to pay a premium for ride-hailing.

We must consider the issue from the perspective of the driver as well. Horan and other critics have raised concerns that ride-hailing companies might be reducing wait times by flooding the streets with empty cars. The general story is that ride-hailing companies are either directly subsidizing drivers, or worse yet, they trap drivers by persuading them to borrow money to buy cars that they must drive for several years to pay off, even if the market is oversaturated and they do not end up earning minimum wage.

This is a serious issue; if this is the case, then the strong preference for ride-hailing we observed from riders is not a story about technology, but actually a story about powerful organizations tricking and exploiting vulnerable workers.

We have already documented that city governments have exploited taxi drivers in the past, convincing them to borrow to buy expensive taxi medallions with the promise that the medallions would magically rise in value in the future. Medallions are not real productive assets, but rather represent a share of a cartel. The only way for medallions to rise in value is by allowing the cartel to extract more wealth from future riders and/or future medallion buyers.

Ride-hailing may have been the proximate cause of the collapse in medallion values, but ponzi schemes such as the medallion racket are inherently unstable. There is no reason to believe that future riders or future medallion buyers would necessarily have consented to participate in this arrangement, even if ride-hailing had never come along.

High current “returns” to medallion owners proportionally raise the necessary level of future wealth extraction from future consumers, which in turn raises the incentive for consumers to vote to terminate the entire arrangement and leave the last generation of medallion owners holding the bag. We observed that this is perhaps beginning to happen in big city housing markets, which are massively inflated by the artificial scarcity of building permits; younger voters are slowly realizing that they are being asked to prop up a pyramid scheme.

The taxi medallion scheme took place in many major cities, most tragically in New York, which saw a spate of driver suicides, and where drivers recently concluded a hunger strike to extract debt relief.

The story the ride-hailing companies tell is that software is much better than humans at matching drivers and riders, paying drivers to go to where demand will be and charging riders extra for rides to areas where there will be few pickups. They also argue that their system lowers barriers to entry for new drivers, bringing on lots of part-time drivers who already own a car and pay for insurance, which makes it easier to balance supply and demand in busy periods.

We should be able to partially test this model by examining the utilization rate of taxis and ride-hailing vehicles. The utilization rate is the percentage of time a driver spends with a paying passenger, as opposed to driving around in an empty car. If ride-hailing apps are truly effective, we should see high utilization rates. If they are lowering wait times by flooding the streets with empty cars, we will see low utilization rates.

The most cited study of utilization, by Princeton’s Alan Krueger and Judd Cramer, was published with data from 2015, very early in Uber’s history. As we see below, it showed much higher utilization rates for Uber in most cities, except in New York, which as we have seen is uniquely dense enough to support high utilization for taxis.

More recent studies, conducted in Seattle and New York to analyze driver compensation, continue to find high ride-hailing utilization rates. This intuitively makes sense; computers should be much better than human dispatchers at organizing drivers to maximize efficiency, and they are widely used elsewhere in logistics for this purpose.

We also want to test whether ride-hailing apps are achieving high service levels and low prices by tricking and exploiting drivers. There is a massive debate on the proper way to regulate compensation and benefits for ride-hail drivers, with both sides marshaling volumes of economic research purporting to show driver compensation.

It turns out that measuring effective driver compensation is difficult because it is sensitive to the method used to estimate driver expenses. Furthermore, many studies rely on survey data, which is likely to be heavily skewed by the incentives of the organization that produced it. Even the ride-hailing companies themselves lack good data, since many drivers drive for multiple platforms simultaneously and each company cannot see what a driver is doing on another app.

James Parrott and Michael Reich did a study in 2018 for New York to justify the minimum wage law for ride-hailing enacted by New York in 2019, and a Cornell team did a study of ride-hailing in Seattle in 2020, commissioned by the ride-hailing companies to oppose a proposed minimum wage rule there (which was passed anyway). Both were done with actual trip data from all of the different ride-hailing apps, so they avoid the issue of unreliable survey data, and they were done for opposing reasons, which might neturalize bias issues.

The general conclusion seems to be that ride-hailing pays comparably to taxi driving and other minimum wage-type jobs. Parrott and Reich followed up in 2020 to show that the New York minimum wage generally had little impact on the price and volume of rides, and perhaps modestly increased total driver compensation. This is consistent with the idea that ride-hailing drivers were already usually getting paid minimum wage or higher. (The policy is still controversial; Uber and Lyft had to ration driver access to the app to ensure every trip complied with the policy, upsetting drivers who were locked out.)

The majority of New York households do not already own a car, which makes New York an outlier; most drivers in New York have to purchase or rent a car to drive for the ride-hailing apps, resulting in a mostly full-time workforce. Most Seattle households already own a car, and the Cornell team found that only 5% of ride-hailing drivers in Seattle worked for over 40 hours a week, accounting for only 17% of all hours worked. This is somewhat consistent with the argument that the ride-hailing apps are largely tapping into a new part-time workforce that is earning extra side cash and squeezing more use out of an asset they already own.

The Cornell team found that the median ride-hailing driver in Seattle earned $23/hour after expenses, a finding that was challenged by Parrott and Reich, which had been commissioned by Seattle to do their own study to support the new minimum wage. Even if the true average effective wage is a bit lower than $23/hour, it seems unlikely that it is much different than what taxi drivers earn, similar to New York.

The debate over the labor policies of the ride-hailing apps and the proper role of regulation will go on, and is far beyond the scope of this essay. We certainly cannot rule out the possibility that the ride-hailing companies sometimes take advantage of drivers. We want to understand the value of the software, and the evidence seems to indicate that the software is effective enough so that ride-hailing companies, riders and drivers can all benefit.

It appears that ride-hailing is a sustainable business. This is good, as I personally have become quite reliant on Uber and Lyft over the years. Yay!

Horan’s narrative aligns with what a certain audience wants to believe, and as a result probably gets more coverage than it would otherwise. There is a certain type of person that wants to believe that every purported new innovation is actually useless, and a cover for a techbro conspiracy to exploit the masses, and that the facade will collapse at any minute. (“Taxis. You invented taxis.”, etc.)

In reality, even though some technological advances fizzle or turn out to have massive drawbacks (like leaded gasoline), most new technology improves the standard of living for society, and is in fact almost the only way we can raise living standards for everyone. Replacing taxis with ride-hailing apps does not offer the same leap as replacing trains with jet airplanes, but even small innovations add up.

In Horan’s defense, his thesis was fairly coherent and he offered testable predictions. Back when he wrote his first piece in 2016, available data was limited, but now it is easier to test.5 If you are not wrong sometimes, you are not generating interesting ideas. You only need to be a successful Cassandra once to hit it big and offset a dozen incorrect crank theories.

This does not mean Uber and Lyft are good stocks. With the caveat that this essay is not investing advice, it does indicate you might be able to scour public datasets and conclude that Uber and Lyft have a lot of untapped pricing power, and there is a path to high margins, perhaps even high enough to justify their current stock prices.

Even if they do have untapped pricing power, you have to assess the competitive dynamics to ascertain whether they will ever realize it. Are consumer habits sticky enough to dissuade both companies from waging price wars, or is it the airline industry all over again?

Then you have to ask whether regulators will actually allow them to raise profits; local governments have already shown an interest in regulating food delivery take rates, and they are also interested in regulating driver earnings. Then you have to ask about the threat of self-driving cars - if self-driving cars become a reality, perhaps the first company to successfully develop a self-driving car will build their own app and undercut Uber and Lyft. (What’s the value of an app that matches drivers and passengers if you don’t need drivers?)

There are a lot of write-ups of Uber and Lyft on the internet - here is a good recent one from MBI, but there are many more in the usual places. Ben Thompson has several older articles on ride-hailing that dive into his view of the economics and have held up well. Undoubtedly there are some useful sell-side reports as well.

It is useful to build the habit of working out the levers that go into determining the long-term economics of a business from scratch, whether you are an entrepreneur building your first slide deck for investors, or if you are an experienced investor trying to get a handle on a complicated business. Then, later on, you can see if the data matches the prediction of your model, and adjust your model as needed. Hopefully this case study is useful as a guide to start thinking about that for your own investments or your own business.

(Disclosure: I don’t own any Uber or Lyft stock, nor do I know anyone that works at those companies, nor do I have any particular expertise in ride-hailing or taxis. This is merely intended to be an exercise with public data to show how one might go about thinking about a new industry. If there is anything important about ride-hailing that I am overlooking (which is quite likely), please note it in the comments and I will edit this as appropriate.)

(Edit: A couple of topics that came up from feedback:

There are two very different groups of ride-hailing critics. They both think that the apps are exploiting workers. However, one group (the Horan cohort discussed in the article) thinks that the ride-hailing apps are inefficient. The other group, the Parrott and Reich cohort, thinks that the apps are very efficient.

If you think the ride-hailing apps are inefficient, then your implicit belief is that if we tax and regulate them, that will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back and they will collapse. (Horan tries to develop an out whereby maybe the apps are engaging in predatory pricing to try to drive the taxis out of business before that happens, but as we can see in the data (pre Covid at least), they’ve barely made a dent in the number of taxis in NY or Chicago after spending tens of billions of dollars - they have huge market share but it’s all new, people substituting away from rental cars or public trans or taking new trips. The idea that they would easily totally drive taxis out of business never made sense if you’ve actually taken a taxi or Uber at the airport or in Manhattan - street hail is often faster than any app and when you are at the airport, you just have to take whatever you can find.) This is a totally coherent opinion to have! Regulators spot businesses that are mere regulatory arbitrages all the time, and regulate them out of existence without a second thought. This happens in finance for example.

Most *serious* ride-hailing critics are like Parrott and Reich in that they think ride-hailing apps are *very* efficient and we should regulate them to make sure they share their oligopoly profits. If you read Parrott and Reich, they are very explicit in laying out their case that Uber and Lyft are in fact *already* very profitable and that they are hiding their profitability with their investments in self driving cars and in overseas affiliates and scooters and so on. (Their NY study was written in 2018.) Their whole case is that it is fine to tax ride-hailing and impose a minimum wage *because* the apps are so efficient - the cost will end up coming out of the apps’ allegedly huge hidden profit margin - and as noted in the article, they ended up being correct that it would not really affect riders, although that is not to say there is not a lot of controversy about the policy still. The key point is that careful regulation makes the most sense if the apps are really efficient and useful because you want the companies to share the surplus, and if they aren’t really efficient and sustainable, you can write crude regulation because anything will drive them out of business anyway and we should all be fine with that.

There was once a time when people used to argue that Amazon would shrivel up as soon as they were forced to pay sales tax. It’s important to remember that a company with an advantaged business model might also be benefiting from regulation and tax preferences, but if you take away the preferences, they will still have an advantaged model and they won’t go away.

This essay is really just supposed to be a case study in how to use revealed preference to get a sense of pricing power - I don’t want to wade to much into the regulation debate - but this is an important distinction that sometimes get lost. I focus here on the “is it sustainable” because I am trying to create a case study that can be applied to other businesses but if you want to take ride-hailing or food delivery regulation seriously, you have to engage with the stronger case which is that we have to assume the apps are not only sustainable but already very profitable (or going to be very soon) and we should regulate on that basis.

A second point that got cut from the essay but maybe shouldn’t have - taxis really get a disproportionate share of their revenue from airports at this point, and the graph does not capture that well because it shows *number* of rides. Airport pickups are far more expensive than normal rides, more than triple the cost usually, so if the graph shows that 17% of taxi pickups are coming from the airport, that means 40%+ of revenue is coming from the airport (and that is only from the airport - that does not even include rides *to* the airport). If you read the reporting now in some cities, it seems like taxis are mostly just camping out at the airport and they can usually make enough to scrape by if they just wait to pick up people who are stranded when ride-hailing cars run out or become super expensive due to surge. That might not be sustainable if we ever get to a post-pandemic world and drivers come back, but that seems to be the case now.

I found this via a Byrne Hobart tweet, where he also correctly points out that the author also picks and chooses when delivering criticism of Uber’s non-GAAP adjustments.

This does not constitute investment advice; industry economics change. Warren Buffett hoped so when he invested in airlines in 2016, quoting Chicago Cubs broadcaster Jack Brickhouse, who once said, “Hey, anybody can have a bad century!” before the Cubs snapped a 108-year long drought by winning the World Series that year. In hindsight, Buffett was a bit early, and he sold his investments at a loss in 2020 after the pandemic hit, but the industry might eventually turn it around, who knows.

Warren Buffett observed in 2002: “If a capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk back in the early 1900s, he should have shot Orville Wright. He would have saved his progeny money. But seriously, the airline business has been extraordinary. It has eaten up capital over the past century like almost no other business because people seem to keep coming back to it and putting fresh money in. You've got huge fixed costs, you've got strong labor unions and you've got commodity pricing. That is not a great recipe for success. I have an 800 (free call) number now that I call if I get the urge to buy an airline stock.” I call at two in the morning and I say: 'My name is Warren and I'm an aeroholic.' And then they talk me down.” As noted above, he later invested a few billion dollars in airline stocks in 2016 and sold them at a major loss in 2020.

In his original piece about Uber from 2016, Horan states: “Uber passengers were paying only 41% of the actual cost of their trips; Uber was using these massive subsidies to undercut the fares and provide more capacity than the competitors who had to cover 100% of their costs out of passenger fares.”

This struck me as implausible, so I checked his table, which stated that in the first half of 2015, GAAP losses were $987.2 million, and passenger payments were $3,660.8 million. If we define the total cost of Uber’s trips as passenger payments + GAAP losses, then passengers were actually covering 79% of the total cost of their trips (3,660.8/(3,660.8+987.2)), not 41%. I would say even this 79% figure is misleadingly low - recall that UberX was only three years old at this point and Uber was not even a tenth the size it is today - as a significant portion of expenses at the time would be investments for future growth, to pay the teams launching new cities and for user and driver acquisition and so forth, items that would not generally be thought of as part of the “actual cost of [the] trips”.

It appears that Horan confused bookings and revenue, two very different concepts. Yet I found that others would later cite his 41% claim in arguing that Uber has an unsustainable business model.

There is something of a popular narrative that clueless VCs are subsidizing the lifestyles of yuppies by backing large startups that cannot achieve sustainable unit economics, and one day, the bubble will burst. Most startups will indeed fail - that is the nature of entrepreneurship - but few startups reach any meaningful size without being able to cover close to 100% of their costs on each unit sold.

The reason is extremely simple. If you truly do spend $2 for every $1 you take in, the bigger you grow, the more money you will lose. Your losses will accelerate as you get bigger, and investors will flee, and you will die a quick death.

Startups that legitimately lose a lot of money on each sale usually implode when they are relatively small. MoviePass got a lot of publicity, but it only ever claimed to have 3 million subscribers paying $9.95 a month, a run rate of $360 million a year, and it blew up in a matter of months. More recently, Zillow suddenly announced it was shutting down its iBuying operation after taking a $300 million writedown on a few billion dollars of homes it had recently purchased, only three years after it launched.

The notion that VC-backed companies are indiscriminately giving away money is generally harmless enough, and it suits both sides - the consumer gets to feel smug and superior, and the company gets the consumer’s money. The reality is that startups that get to a meaningful size are more likely to fail because they are unable to execute at the same level as their competition than because they have a fundamentally flawed business model that causes them to lose money on every sale.

One of his interesting points is that if this business model is so lucrative, then we would expect similar companies like Domino’s Pizza (which now gets most of its business from its mobile app and has its own delivery fleet) to become very valuable. Indeed, Domino’s ended up being one of the top performing stocks of the decade, as they grabbed market share and expanded margins. With an enterprise value of $25 billion, it is now much more valuable than Lyft.

I wonder if moving towards an auction-type model for driver rates could lower costs. Drivers submit their per-mile rate for the day, and in addition to proximity, a job is rewarded to the lowest bidding driver.

That's why I don't like MBAs. They love talking and publishing copious amounts of research with such baseless claims and comparisons. Comparing Uber with the airline industry and calling the software worthless tells me more about the author than Uber. Ever heard of a marketplace on the web?