It's Never the Subsidies

High speed rail, the subsidy narrative, and the midwit fallacy

You have probably noticed that there is a widely-popular Thing out there in the world. The popularity of this Thing bothers you greatly because you feel that this Thing is inferior, so much so that it should perhaps not even exist at all.

You are aware that there is an Alternative to the Thing that you believe is measurably superior across most important dimensions. It baffles you that most people consume the Thing instead of the Alternative.

Your intuition tells you that if people are consuming the Thing instead of the Alternative, there must be some kind of deception or distortion at work; no rational person would consume the Thing when the more attractive Alternative exists.

You do some digging, and you make a discovery: the Thing actually benefits from subsidies! Of course, it all makes sense now! You knew that no one would consume the Thing unless the playing field was rigged. If we stopped subsidizing the Thing, we would all be living in a utopia where everyone happily consumes the superior Alternative, and society would be free of the wasteful subsidies being directed at the Thing.

You assemble your narrative, explaining to the world how we have all been deceived, and how nefarious forces have conspired to foist the inferior Thing upon us, preventing us from enjoying the irrefutable benefits of the Alternative.

The logic of your narrative goes like this:

The Alternative is measurably superior to the Thing across some dimensions. You can go into deep, deep detail on this, because you are passionate about the Alternative.

The Thing receives subsidies. You can usually easily prove this too, and you can go on at length on the subject.

You therefore conclude that if the Thing did not receive subsidies, we would all be happily consuming the Alternative.

This narrative often sounds compelling, usually because points (1) and (2) are fleshed out with considerable detail that was not previously known to the reader. (You know A LOT about both the Alternative and the Thing.) This leads the reader to assume that the overall logic of your narrative is sound.

Also, some readers will have had the same intuition you had, and so they will not question your logic; they always suspected they understood the true nature of the Thing, and you are supplying evidence that confirms their priors.

However, the logic of the narrative is clearly incorrect. (1) and (2) do not imply (3).

No one cares if the Alternative is better than the Thing across some dimensions, if it is worse than the Thing across other, more important dimensions. For example, the Alternative might be high quality, but unaffordable.

It is all fine and well to show that the Thing is receiving some subsidies, but it is crucial to show the magnitude of the subsidies is big enough to plausibly swing people from the Alternative. For example, a 5% tax or a 5% subsidy probably won’t move consumption much either way.

This is all a bit abstract, so let’s look at a couple of concrete examples. Let’s start by revisiting one we looked at last year:

The thesis behind ride-hailing (e.g., Uber or Lyft) is that it is a straightforward application of mobile computing that provides a superior and more efficient alternative to traditional taxis. Software is cheaper and more accurate than a human dispatcher when matching riders and drivers, so ride-hailing drivers will spend less of their time driving an empty car looking for a ride, while riders will spend less time waiting for a driver. Also, software provides an additional layer of transparency, enhancing the rider and driver experience: riders can see where the driver is as they wait, and report bad drivers, while drivers can do the same for riders.

Since software is almost costless to replicate, it does all of the above at a negligible per-ride cost, given enough scale. Since software provides a much better outcome at a much lower cost, we can expect ride-hailing to mostly replace traditional taxis and human dispatchers, in much the same way that software has mostly replaced bank tellers and switchboard operators.

This thesis has its detractors; some people see ride-hailing as unsustainable. To them, ride-hailing is the Thing and taxis are the Alternative. Their thesis goes like this:

Taxis basically provide the same service as ride-hailing, except they don’t have to incur all of the corporate overhead and technology expense of an Uber or Lyft.

Ride-hailing only exists today because dumb investors subsidize their losses, in the belief that they will drive taxis out of business and reap monopoly profits afterwards.1

Ride-hailing is therefore unsustainable and will disappear when investors come to their senses.

Let’s sanity check this thesis. First, how much market share has ride-hailing claimed from taxis? Well, the excellent Todd W. Schneider has created public dashboards based data released by the New York and Chicago, so that’s an easy question to answer. Here is the data for New York:

Ride-hailing apps have a dominant 84% market share in New York, up from zero a decade ago. He has ride-hailing at over 90% in Chicago. These are two of the biggest markets for ride-hailing, so they should be fairly representative.

Next, we want to see how much the ride-hailing companies are spending to subsidize rides. Uber is by far the biggest player, so it should be sufficient just to look at them. If we go to their latest quarterly investor report, they lost $713 million on total bookings of $29 billion – so they are currently subsidizing riders (and food delivery customers) to the tune of 2 cents on every dollar.

Now we have to ask ourselves, what is more likely:

Ride-hailing went from 0% to ~90% market share because it provides a better service at a lower cost by replacing a manual approach with software, or;

Ride-hailing went from 0% to ~90% market share because ride-hailing companies are subsidizing 2% of the total cost of rides.

This quick sanity check reveals the logical flaws with the ride-hailing-skeptical narrative. It’s true that taxis are superior on some dimensions, and it’s true that Uber and Lyft subsidize rides. But the subsidies are far too small to possibly explain how ride-hailing captured 90% of the market in a short period of time, and so we have to conclude the ride-hailing dominates the market because it has a superior model.

Via Byrne Hobart, Casey Handmer brings us a lengthy essay entitled Why high speed rail hasn’t caught on. The context is the recent NYT article on the woes of the California high speed rail (HSR) project. Handmer argues that high speed rail is fundamentally uncompetitive with air travel, mostly due to physics.

He concludes:

HSR is not a compelling option for generic high speed intercity transport.

His claim is surprising. To be sure, high speed rail is only competitive on shorter trips, where the cost and hassle of getting to and from the airport at each end outweighs the direct speed and price advantage of air travel. But high speed rail has been built extensively where cities are located close to each other, and wherever high speed rail is built, it mostly displaces air travel:2

In fact, the evidence suggests that it is air travel that hasn’t caught on on these shorter routes, limited to capturing passengers that are already near or at the airport (e.g., connecting from another flight). Short plane trips are mostly used between city pairs with no rail option, such as between Los Angeles and San Francisco. This chart from France suggests that rail is dominant for all rail trips under four hours:

Ah, but what about the subsidies? The subsidies, the subsidies! Here is Handmer again:

Japan’s ostensibly private rail companies have gone bankrupt and been bailed out so many times I’ve lost count, racking up billion dollar yearly deficits year after year. Indeed, as far as I know there isn’t a single HSR route anywhere on Earth that operates profitably on ticketing revenue, and so operation always requires substantial subsidies.

Ok, so, let’s check the subsidies. The high speed rail operators publish their numbers, so this should be easy.

Let’s start with Japan. JR Central is a $20 billion public company whose main business is operating the bullet train from Tokyo to Nagoya to Osaka; they estimate that their operating area covers 60% of the population of Japan.

Their 2019 annual report shows $6.4 billion of operating income on $17.1 billion of revenue, almost entirely from high speed rail. There is no mention of operating subsidies, and in fact it has consistently paid increasing dividends over the last two decades. Their 2019 ROIC clocks in at a respectable 10%.

Let’s move on to Europe. France’s high speed rail operator, Voyages SNCF, reported a € 483 million 2019 profit on revenue of € 8.0 billion. Again, no mention of subsidies or grants. Further north, Eurostar rung up £92 million of profit on £987 million in revenue in 2019, no subsidies there either.

How about the US? Amtrak claims that the Acela brought in $662 million in revenue in 2019, against only $328 million in expenses, for a profit margin of over 50%. (Unlike the Japan and Europe examples, the Acela is not a separate operating segment, so this figure probably does not include track depreciation and thus is less comparable.)

I am not sure what subsidies Handmer is referring to. He is correct that Japan subsidized their rail operator decades ago, but that appears to have gone entirely toward artificially low fares and unnecessary employees, rather than having anything to do with the fundamental economics of high speed rail.

The transportation researcher Alon Levy also says that high speed rail is profitable in Europe and Japan, so I do not think I am missing anything. The most charitable reading is that high speed rail indirectly benefits from some subsidies on local routes, which provides some feeder traffic, and from government coordination to get the right of way to get it built in the first place, but once built it tends to be profitable given sufficient demand.

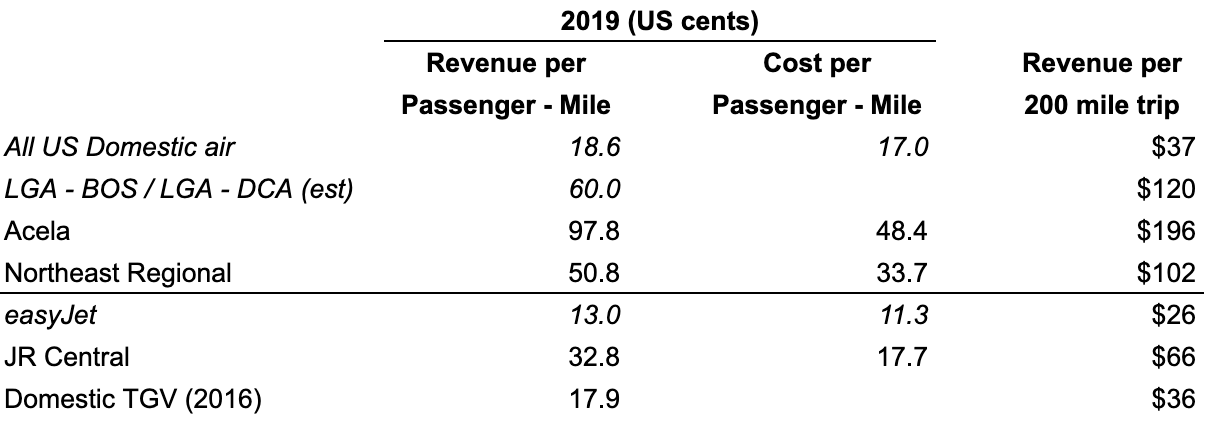

Handmer is probably correct that high speed rail is more expensive than air on a per mile basis. Here are the figures I got from 2019 annual reports:3

It appears that high speed rail is more expensive on a per-mile basis, but not by enough to be meaningful on a typical 200 mile trip. Even going from 13 cents to 33 cents per mile only tacks on an extra $40 to the cost of the trip, not enough to compensate for the additional cost and hassle of making an additional airport trip at each end. The Acela is popular despite charging nearly $1 per mile.

The evidence suggests that it is a mistake to focus on speed and cost when evaluating rail. Rail is dominant on most shorter routes despite the higher cost and slower speed vs. air. The evidence indicates that people pick rail because of convenience and comfort, and are willing to pay a premium for a slower trip to get it.

Again, the simple explanation is the correct one. High speed rail is politically popular because people far prefer it over air travel, and we know this because it almost completely displaces air travel wherever it is built.

The subsidy narrative is a good example of the Midwit Fallacy we discussed previously. The Midwit Fallacy describes our tendency to reject simple answers and accept complex answers simply because complex explanations sound smarter. We do so even when the complex answer is contradicted by the available evidence and contains logical holes.

Here is a sampling of other related areas where you sometimes see people make a contrarian midwit case that Thing X is only popular because of subsidies:

Home ownership. Yes, the US showers homeowners with subsidies, but our home ownership rate of 65% is very much in line with other countries. People want to own their homes regardless of subsidies.

Car ownership. This has a bit more truth; we subsidize car owners in a multitude of ways, while other countries tax them heavily, which leads us to drive a lot more. However, cars are unmatched for their convenience and flexibility, and so car ownership in other countries is not far below what it is here in the US: in 2022, Americans owned 868 cars per 1000 residents, while Japan and Western Europe are in the 600-750 range.

Single family homes. People also like living in suburbs and in single family homes. Yes, single family zoning does limit the construction of multifamily housing in the US, which massively inflates rents and condo prices in popular cities, but single family homes are popular everywhere. In the EU, 53% of the population lives in single family homes (not all detached), while almost 70% of housing is single-family in the US.

Here is why the subsidy narrative is generally likely to be wrong:

Politicians like to subsidize popular things. That gets them more votes than subsidizing unpopular things. The subsidy narrative usually gets the causation reversed – the Thing is not popular because it is subsidized, the Thing is subsidized because it is popular.

In most cases, to get the majority of people to switch from a vastly superior Alternative to an vastly inferior Thing, the magnitude of the subsidy required would be tremendous. Like, implausibly tremendous. A small subsidy will nudge a few fence-sitters, but that’s usually all.4

Most importantly, handing out tremendous subsidies for something that is widely popular is impossibly expensive, simply because it is widely popular.

If the country only consumes a million widgets a year, a $100 per widget subsidy is manageable – $100 times a million is only $100 million. If the country consumes ten billion widgets a year, that’s a less manageable $1 trillion per year.

You can hand out small subsidies for popular things (like mortgages), and large subsidies for less popular things (like electric cars), but it is almost impossible to afford large subsidies for popular things. Incidentally, this is the exact impossible dilemma many countries are having to confront with energy prices this winter.

This case is unusual in that it is not the government giving out subsidies, but private companies, which are doing so to build consumer habit and economies of scale that they hope to profit from later on.

The European data comes from this 2020 paper by Arie Bleijenberg, via Alon Levy, who has additional notes about air vs. rail. The Japanese data comes from page 2 of JR Central’s 2019 annual report. The US data is from this 2015 DOT study.

The exception is the TGV data, which is from a nice find by Alon Levy in a French-language report. In general, European continental high speed rail fares seem in line with France.

If instead of subsidizing the Thing you actually ban the Alternative, that will definitely swing demand much more.

Good stuff as usual, i read every one of your articles, keep up the good work.

One recommendation i have is would you consider incorporating more Chinese company analysis or as examples in your articles? For instance, when discussing ridehailing, DIDI may worth looking into in comparison to Uber and lyft, and for subsidies, all major chinese Internet platform practice subsidies in one form or another (BABA, meituan, PDD, etc), or for high speed rail, China now has the longest high speed rail network in the world and there are several listed operators. Would be nice to have an idea how the Chinese counterparts compare to global peers.

Just found your stuff today and I've been having a great time reading all of it. Thank you!