Do We Want High Home Prices?

Never reason from a price change

Recently, President Trump gave his view on housing prices:

“There’s so much talk about “oh we’re going to drive housing prices down”. I don’t want to drive housing prices down, I want to drive housing prices up, for people who own their homes. And they can be assured that is what’s going to happen.

Which begs the question: do we want housing to be cheaper or more expensive? Two-thirds of households own their own home, and 60% of homeowners carry a mortgage, so it would seem that higher housing prices are better for Americans. But some would argue that there is a paradox here, because most young people do not yet own a home and wish to eventually buy one, and higher housing prices lock them out of the American Dream.

This is a tricky question, so let’s start by asking a simpler question: are we better off with higher oil prices or lower oil prices? Most people would intuitively answer that we are better off when oil prices are lower. High oil prices mean high gas prices, and the less money we spend at the pump, the more money we have to spend on everything else. Another way to think about this is that we are all short oil — that is, we have to buy oil in the future at the market price — and lower oil prices reduce the future liability of our collective short position.

But are we really better off when oil prices are low? Falling oil prices are sometimes associated with severe economic downturns. Oil peaked at $140 per barrel in 2008 and fell to $40 in 2009, after the financial crisis. Oil began 2020 at $50 per barrel but briefly plummeted below zero that April after Covid hit. The converse is true as well: oil prices often rise when the global economic outlook brightens.

This happens because supply and demand are not that responsive to price in the short run — it takes a while to drill new wells or improve the average fuel efficiency of the cars on the road — so when global incomes rise or fall, the demand curve abruptly shifts, and oil prices must rise or fall significantly to maintain equilibrium. It is thus common for us to be economically better off during periods in which oil prices are rising. Another way to think about this is that for most of us, our largest asset is the present value and stability of our future earnings (whether that is in the form of wages or dividends or rents), which is tied to the health of the economy. A major recession will save us a few bucks on gas, sure, but at the much greater cost of higher unemployment and lower income.

The problem is that our intuitive framing of the question is flawed. As economic participants, we are used to simply responding to shifts in price. The great thing about prices is that economic participants don’t need to know why a price changed — the new price transmits all of the information and incentive we need to change our behavior.

But as economic analysts, we actually do need to know what caused a price change, because two events can have the same impact on price while having opposite impacts on consumer welfare. We have to think in terms of supply and demand, which allows us to untangle the confusion.

In this example, lower oil prices are sometimes the result of a shift in the supply curve that increases the aggregate quantity of oil that producers are willing to supply at most prices, like the shale revolution that unlocked oil supply in the U.S. in the 2010s. This kind of shift makes consumers better off. Lower oil prices can also be the result of a shift in the demand curve resulting from a deep recession, which generally makes consumers worse off.

As Scott Sumner likes to put it: Never reason from a price change. If we start by implicitly assuming that all price changes have similar causes, we will see paradoxes and contradictions where none exist. It is necessary to trace the root cause of the price change before drawing conclusions about likely impacts.

With this in mind, we can see that the original question about housing prices is simply poorly framed. We can think of cases where higher housing prices are associated with people generally being worse off, and we can think of cases where higher housing prices are associated with people generally being better off.

Let’s start with an example where housing prices go up and people generally end up worse off: restrictions and taxes on new construction. In the US, this can take the form of land use restrictions, years-long procedural delays, new units set aside to be sold at a discount (“inclusionary zoning”), and excessive permitting fees. Normally, when local housing demand rises, prices rise, which causes developers to build more housing, which causes prices to fall back toward the cost of building new housing (at which point developers are no longer incentivized to build).1 Supply restrictions break the usual feedback loop, causing prices to permanently rise far above the cost of new construction, up to double or triple in the most expensive American cities.

If the majority of households own their own home, what is the harm here? Well, similar to our oil case study, remember that we all have a built-in short position in housing services: that is, we all are locked into procuring a place to live for the rest of our lives. One key is understanding that buying a house mostly only hedges this short position — increases in market rent improve your long position as a homeowner, but harm your short position as a future housing consumer by roughly the same amount.2

No matter how much your house goes up in value on paper, as long as you are locked into living in the same place by your career and/or your family and friends, you won’t be much better off in any real sense (at least not in your lifetime). Also, supply restrictions are not even unambiguously good for home values. The value of a house lies in the combined value of the land and structure; supply restrictions are likely to increase the value of newly scarce structures, but strip the ability for a homeowner to realize the full value of their land by demolishing their single family home and building a 20-unit apartment building in its place, if future conditions warrant.

Then you have to consider the households who don’t own, a group that skews younger. (27% of Gen Zers that head a household are homeowners, vs. 80% of Boomers.) Some might have rent control, which economically is a little similar to ownership in the sense that it confers a hedge, but won’t result in a net benefit. The rest simply have the short position with no offset — they face the choice between paying more for housing, or moving to a new city away from family and friends. Even the ones that stand to eventually inherit part of an appreciated home from their parents are unlikely to do so until they are well into middle age, at which point they will have paid inflated rents for years and will have also likely already overpaid for a home. Supply restrictions are usually at best a net zero, and at worst a huge negative.

We can also use this framework to identify specific winners and losers from local supply restrictions. A retiring Boston homeowner that is planning on moving to Florida doesn’t have a short position in the Boston market, and will be a big winner after selling. Another homeowning couple who derives happiness from knowing that their three kids will be able to live nearby with their grandchildren will be a big loser. An event that leaves people worse off on average will create enough variance to have a few individual winners alongside some major losers.

Now let’s look at something that raises housing prices and leaves people better off: higher wages driven by strong economic growth.

Armed with higher wages, people bid up the price of housing. Developers respond to higher prices by building more housing, but recall that developers stop building when the price falls to the cost of construction. Construction requires employing local labor, so higher wages translate to more expensive construction which results in a higher equilibrium price for all housing, though not so much higher that it fully offsets the benefit of higher wages. (Construction also requires the input of globally tradable commodities like lumber, steel and energy, the prices of which will be less affected.) Housing prices go up, and people are also better off, similar to what we saw in our oil example.

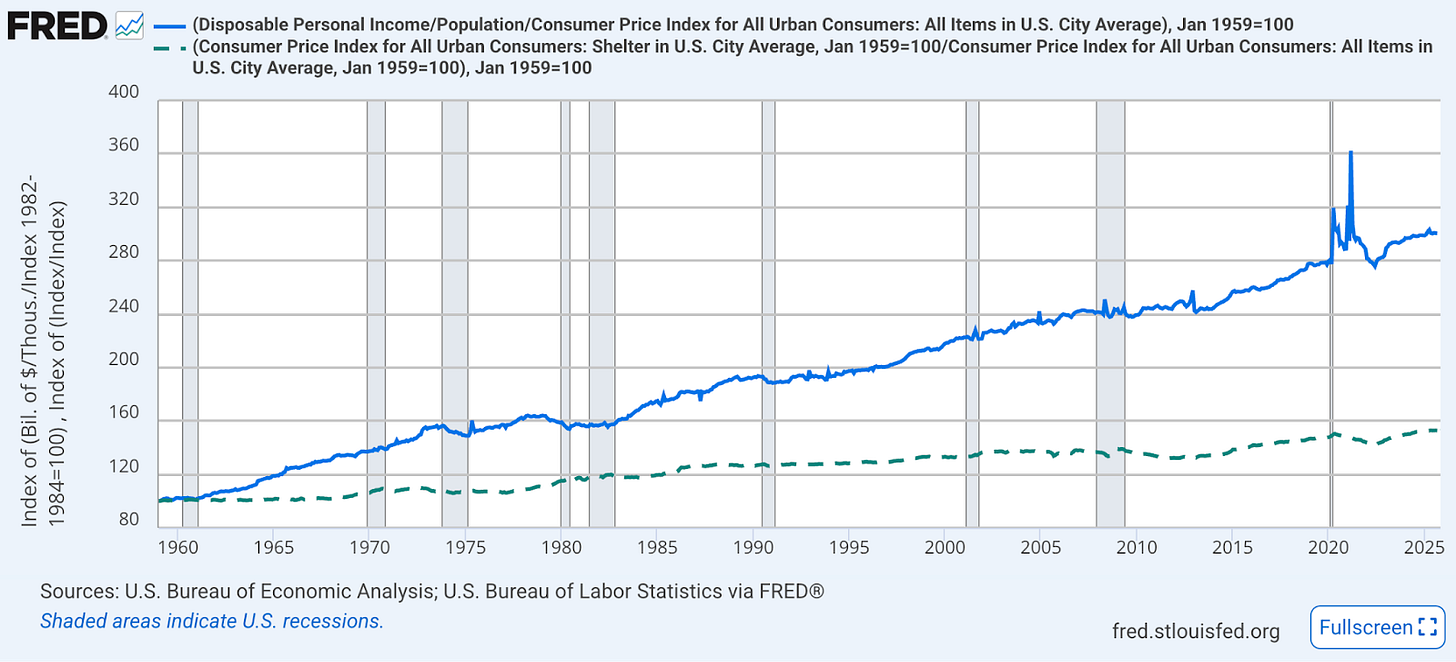

This sounds like a pretty stylized model with lots of arbitrary assumptions, but it actually pretty well matches what we observe over time and across geographies: higher incomes are correlated with higher real housing prices but also higher material living standards and more affordable housing. Within the US, the cost of shelter has outpaced inflation by 50% since 1959, but real disposable income per capita has tripled (see the graph below). Housing prices are higher than they were a generation or two ago, but our incomes today are much higher, so we live in much larger and more modern homes than our grandparents did.

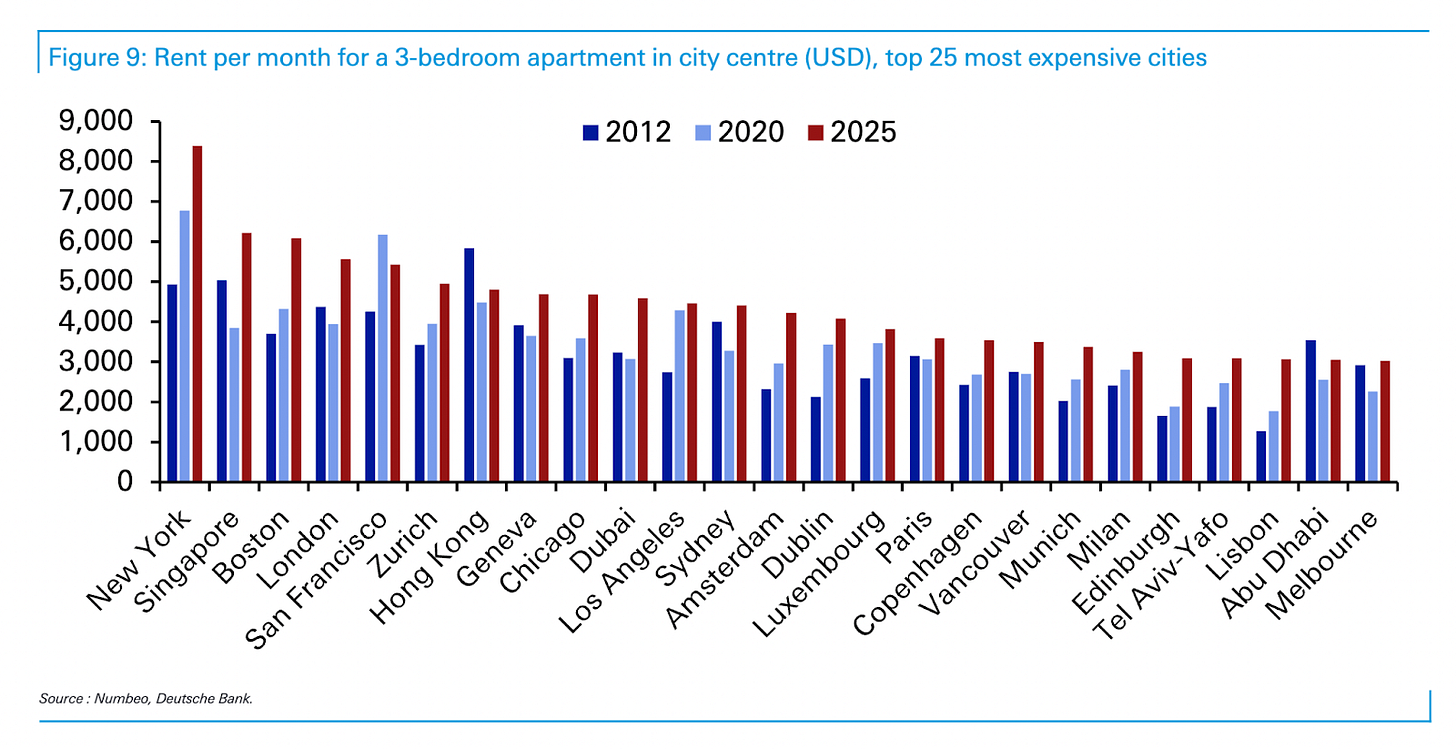

The same pattern emerges when we look across countries. The US is richer than most countries, and so it is no surprise that monthly rents in US cities are among the highest in the world (per a Deutsche Bank survey):

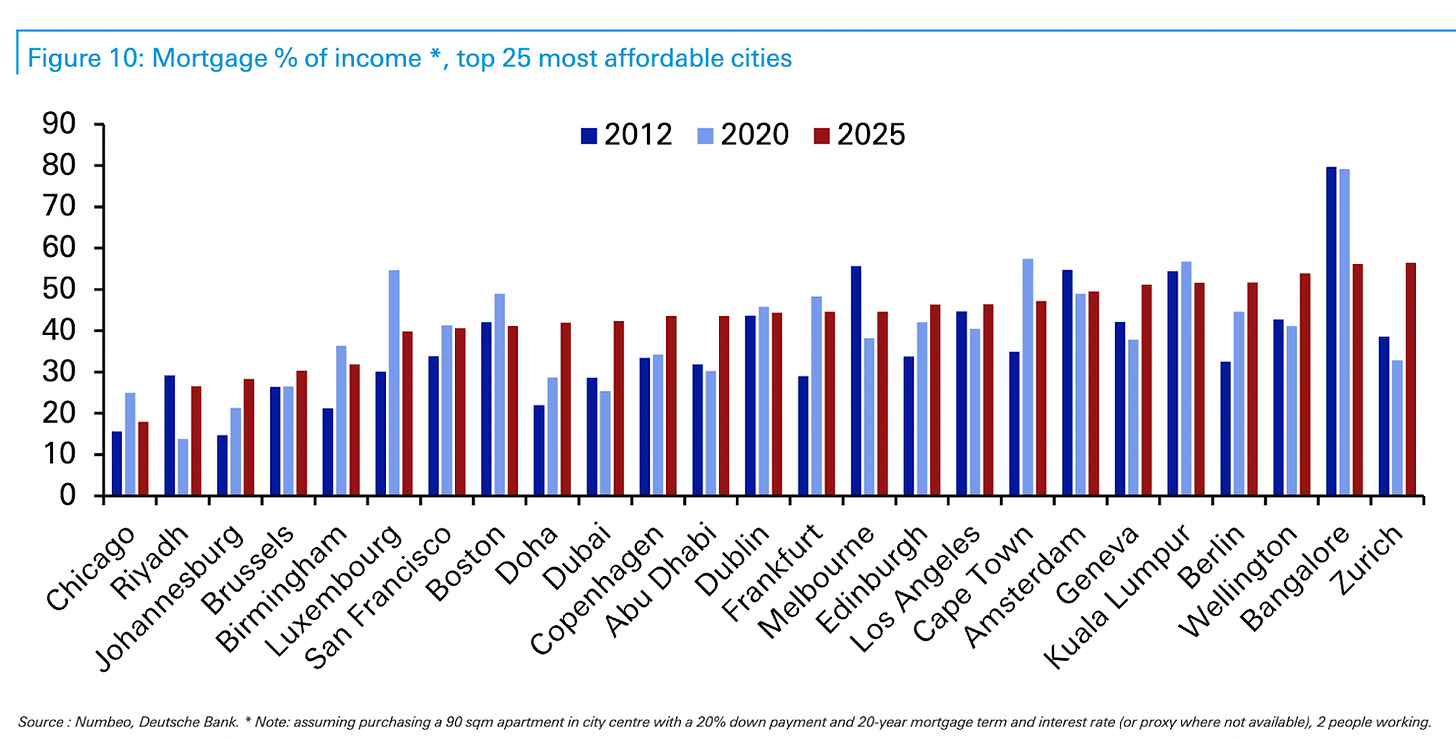

But because the US is so rich, its cities actually rank among the most affordable in the world when considering housing prices relative to income:

Note that Chicago, which has historically been less affected by supply restrictions, actually has the most affordable housing of the 69 global cities that DB surveyed, despite having the 9th highest monthly rents!

We can connect this back to our earlier observation that the most valuable asset that most people have is their future earning power: depending on your age and income, the present value of your future wages is probably millions of dollars, and the value of your future social security benefits is likely at least in the hundreds of thousands (and is fully dependent on future payroll taxes). An event that increases your future earning power in a meaningful way is always likely to more than offset price increases on a limited subset of the goods and services that you buy.

Note that there is something analogous that goes on when people talk about stock prices. People associate higher stock prices with good economic outcomes, because corporate profits are linked to economic growth, and because stock prices rise when people are feeling good about the future. But high stock prices do not have to be linked to good overall economic outcomes: imagine if the government stopped enforcing antitrust law, which would lead to higher corporate profits and higher stock prices but at the expense of higher prices faced by consumers at the checkout counter.

In the US, we channel a lot of our savings into building home equity, so much so that it makes up a disproportionate share of our financial wealth for the median household. This leads many to the natural conclusion that higher home prices necessarily make us better off by increasing our net worth on paper. In reality, higher home prices are only correlated with good economic outcomes if they result from broadly higher incomes, and are a bad thing if they result from supply restrictions. In the latter case, our off-balance sheet (but still economically real) liability of future housing costs rises at least proportionally, more than neutralizing any benefit.

Reasoning about housing from price changes also causes us to mistakenly conflate high housing prices with desirable amenities such as good schools, low crime, and walkability. Neighborhoods that gain these amenities see rising housing prices, and people subconsciously start thinking that desirable amenities and rising housing prices are inextricably linked. Sometimes people even theorize that desirable amenities cannot be allowed to infiltrate poor neighborhoods lest they cause gentrification and price out the locals.

This is the same logical fallacy as before, except applied to different dimensions of existing housing instead of the total quantity of housing. Goods and services are not expensive solely because they are desirable, but because they are desirable and scarce, and the price system is just a way to ration desirable goods and services (and to incentivize their production). If we lower crime in an existing neighborhood, housing prices in that neighborhood will rise but housing prices in other safe neighborhoods will fall because safety is now less scarce.

A common objection is that developers just run out of land, but in practice we can economize on land by building upwards. In practice, land costs are 14% of the sale price of new single family homes (where we aren’t building up) and just a bit higher for multifamily housing (where we are).

Home ownership only hedges you against getting priced out of your neighborhood, which is useful in scenarios where your neighborhood gets much more desirable while your income does not improve proportionally (e.g. if you are retired). It leaves you doubly exposed if you lose your job because your local economy suddenly declines: it wipes a large portion of your net worth at the same time your income goes away.

Another thoughtful and well reasoned piece. Thanks for sharing!

Land cost 14% of new SF home price? Please tell me where so I can go there, buy all the land, and build SF homes for sale! :)

Average real net wages tripled? For whom? Does that FRED chart link to a database from which it crunched those numbers?

Thank you, and keep up the good work!